Curating Close Encounters

Chicago, 2:57 p.m. on Sunday, 12 December 2005. I arrived in a snow-clad Chicago to undertake a curatorial internship at the Museum of Contemporary Art. This opportunity found me being billeted by Chuck Thurow the then Executive Director of the Hyde Park Art Centre (HPAC) and the late Dale Hillerman, a retiree and patron of the Field Museum of Natural History (FMoNH), Chicago. It was through this connection with Chuck that sparked a project that would unfold over another five years and involve eight artists and many others in subsequent years. This project came to be called Close Encounters but before I delve into the specifics it is important that more context is provided to emphasise how a small meeting of artists and curators is only one part of a much larger complex network of people across time as a “trajectory of unfinished stories”.[1]

___________________

The HPAC, is a dynamic community art space and a contemporary art gallery and is recognised as Chicago’s most experimental public gallery, with a similar function to Te Tuhi in Auckland where I currently work. It has been in operation since the 1940s and from the beginning has had a very strong relationship with artists and in many cases has been critical in launching artists’ careers. It is located on the Southside of Chicago, which is an area that takes up 60 per cent of the city and is at least twice the land area of the entire Auckland region.

The Southside has a population of approximately 800,000 that is over 93 per cent African-American and is predominantly a very poor area with a high crime rate. Hyde Park, however, is a small wealthy suburb that is centred around the University of Chicago and has been the home of some of the most famous African-Americans including Muhammad Ali and currently Barack Obama. Although, if you drive a few blocks in any direction you end up in some of Chicago’s most impoverished ghettos. This location gives the HPAC a unique cross-section of people and communities that visit the Center for art classes, community meetings, events and to experience contemporary art. Therefore, engaging with local communities is a primary purpose of the HPAC.

___________________

Chicago, April 2007. I was invited back to Chicago by Chuck to be the HPAC’s international curator in residence with the intention of developing an ambitious artist exchange and experimental curatorial project between the city of Chicago and New Zealand. My residency was also timed to coincide with a delegation of Māori leaders visiting the FMoNH. This delegation were visiting to discuss the museum’s ownership and use of Ruatepūpuke II housed at the FMoNH in Chicago – the only wharenui in North America and is one of just three complete wharenui outside of New Zealand. Under unknown circumstances, this majestic whare was acquired by a German curio dealer and finally ended up in the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Almost a century later, it was ‘rediscovered’ by New Zealanders when the Te Maori exhibition travelled to the FMoNH in 1986.

Now in 2007, Chuck and I attended a pōwhiri held at Ruatepūpuke II and after meeting with members of the Ngāti Porou hapu Te Whānau a Ruataupare (of Tokomaru Bay on the East Coast) and FMoNH's Curator of Pacific Anthropology John Terrell we became very interested in the rich historical connection forged between Chicago and New Zealand. Furthermore, the intersection of that delegation with the museum’s staff, trustees and with the museum’s visitors embodied many of the complex cultural issues that are the root of divisions and confrontations in this global age. We saw, in both the emotion and civility of this interaction, a model by which to challenge a group of artists from New Zealand and Chicago to tackle the persistent issues surrounding the divisions of different social groupings and their function in a multicultural society – an issue so pertinent for organisations such as the HPAC who service a great diversity of people.

We were also driven by the desire to create a situation through which new forms of engagement might emerge and also by bringing artists from these two nations together because of their striking similarities and dissimilarities. Both countries were colonised by the same European culture, which imposed its value system upon sophisticated existing cultures that at the time were identified as ‘primitive’. At the same time, the two current countries are both literally and figuratively at opposite ends of the world. As a consequence, the dialogue we hoped might emerge among the artists and curators would be unlikely to rely on familiar formulas and more likely to encourage new forms of practice.

Following this motivation, we then proceeded to select artists not just for our strong belief in their practice but also to assemble a group who were from a variety of different social/cultural backgrounds to ensure dynamic participation. These were United States-based artists Tania Bruguera, Juan Angel Chávez, Walter Hood, Truman Lowe and four New Zealand-based artists Daniel du Bern, Maddie Leach, Lisa Reihana and Wayne Youle.

The central aim of Close Encounters was to explore social gatherings and their venues, with the objective of encouraging new forms of engagement between artists, art institutions and communities. In his study of cafes, pubs, bookstores and other ‘hangouts’, Ray Oldenberg emphasises the importance of social gathering spaces to community coherence. He argues that these gathering spaces can not only encourage communal synergy but also creative problem solving – problem solving that can lead to significant community and cultural transformation.[2]

The history of social engagement art projects has shown that the arts can also generate similar results.[3] This latent potential, however, raises a raft of questions that Chuck and I asked the artists to debate: Can cultural gatherings be both inclusive of other groups and retain tradition? To what degree does the design of physical space mediate or influence social interaction? And, if contemporary artistic practice has proven to generate both constructive and disruptive social encounters, what ethical responsibilities do artists have to society?

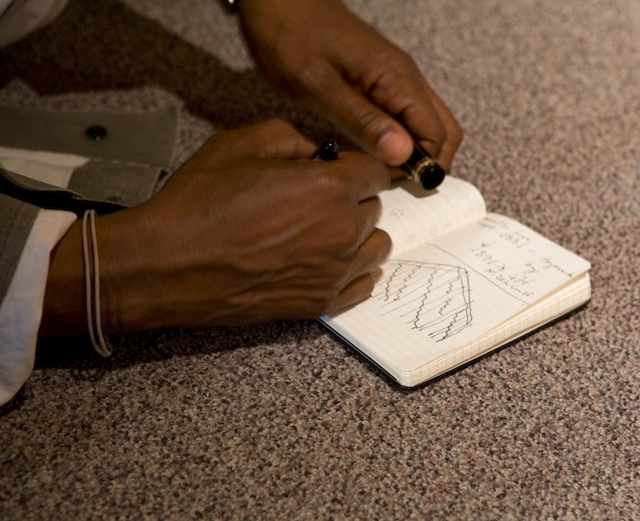

To provoke these questions we decided to expose artists to a diversity of community and social gatherings – with the idea that the artists’ experiences would be shared, debated and finally explored through their artistic practice. To achieve this goal, we planned to follow a discursive model in which artistic and curatorial development would evolve simultaneously.

It was hoped that this open-ended and adaptable approach would birth new perspectives and experiences of culture and prove a rigorous challenge to both artistic and curatorial practice. We were aware that it is a great challenge to lump a whole set of challenges on to a group of artists in the expectation that they would go forth and expand upon them. Therefore, we put considerable effort into giving the artists a series of experiences as a starting point.

___________________

New Plymouth, early one morning sometime in April 2008. It is pitch black and I am standing confused and anxious in the middle of my lounge. I am confused because for some reason I have a taiaha in my hands that I am violently and involuntarily thrashing in all directions. While I cannot see because of the thick darkness, I know that Chuck is also in the room and I am frightened that my uncontrollable aggressive actions might injure him. In the morning, I realise the significance of the dream. I have ventured into something that I have knowledge of but lack true understanding.

___________________

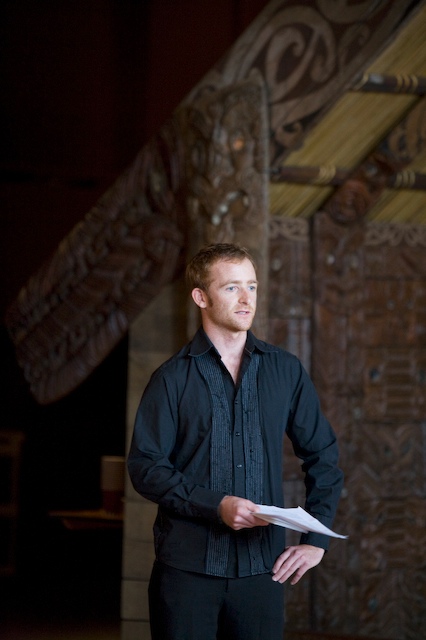

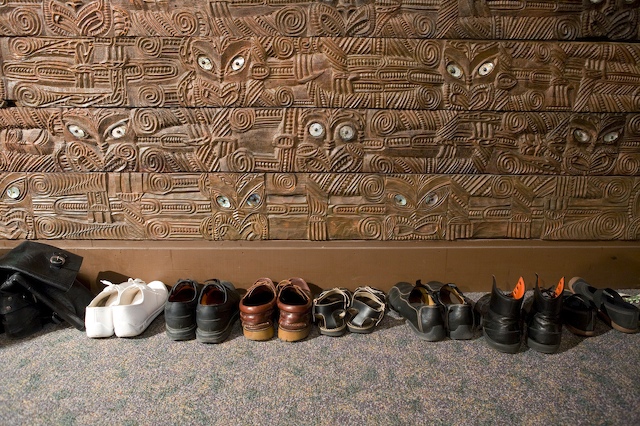

Ruatepūpuke II, 9 a.m. on Thursday, 15 May 2008. Spine tingling karanga echo through the FMoNH as we walk past displays and vitrines until finally we are standing under the gaze of a hundred soul-piercing pāua shell eyes. This is the pōwhiri signalling Phase One of the Close Encounters project. The idea of having Ruatepūpuke II as a point of gathering came about through the desire of Te Whānau a Ruataupare the original owners. Te Whānau a Ruataupare have been working with the FMoNH for the last couple of decades since the Te Maori exhibition, not to repatriate the whare but to make it a living and functional space rather than a relic within a museum collection.

Under the guidance of the hapū represented by Erū Wharehinga, Director of Mātauranga Māori Arapata Hakiwai from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongawera, and Director Joe Podlasek of the American Indian Center (AIC), Chicago, we were the first visiting group to commence a hui under the appropriate tikanga. For Ruatepūpuke II was also the perfect place to contemplate the role for artists within community – as the whare is itself an amazing work of art that embodies the wairua and function of its original community.

Not only did the pōwhiri ceremonially start the Close Encounters project but it also played an integral role in building and healing the relationship between Te Whānau a Ruataupare the AIC and the FMoNH. Before Close Encounters, these groups did not have clearly-defined roles or a cohesive understanding of their part in making Ruatepūpuke II being a living space. Therefore, Chuck and I often acted as mediators between all three groups by keeping lines of communication clear and open.

In preparation for the Close Encounters project, the FMoNH also fast tracked major renovations to the display of Ruatepūpuke II to make sure that the area was suitable for such a culturally significant event. This included reconstruction of the exhibition space to create a marae ātea and to expose hidden windows that hadn’t been opened for a number of years, allowing natural light to illuminate the space. This major alteration was agreed upon between the FMoNH and Te Whānau a Ruataupare in previous years but had not been acted upon. The instigation of Close Encounters gave significant reason for these renovations to become a reality.

The FMoNH, like other large traditional museums around the world, maintains a conservation policy of exhibiting artefacts in controlled environments – typically without natural light in favour of artificial lighting. Now that the windows have been uncovered, it is possible to see Chicago’s skyline, allowing museum visitors to view Ruatepūpuke II in the context of the city of Chicago. These changes made to the area surrounding Ruatepūpuke II shows a commitment by the museum to keeping the spirit and cultural significance of their treasures alive in the present.

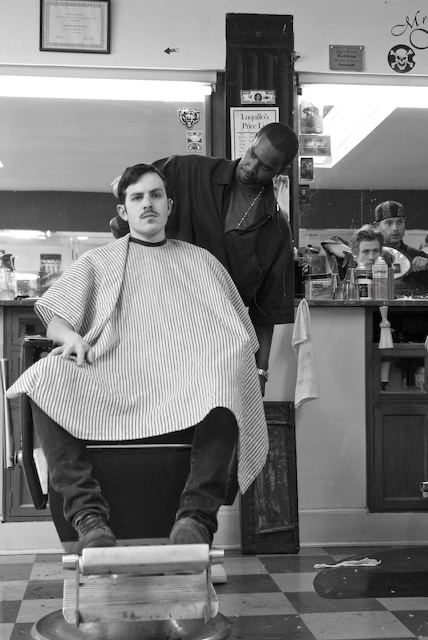

Photos by Michelle Litvin, courtesy of the Hyde Park Art Centre, Chicago.

To introduce the New Zealand artists to the racial issues of the United States we decided to visit two leading exhibitions on the topic that were being shown at the time. These exhibitions included Black is, black aint at the Renaissance Society and Disinhibition: black art and blue humour at the HPAC.

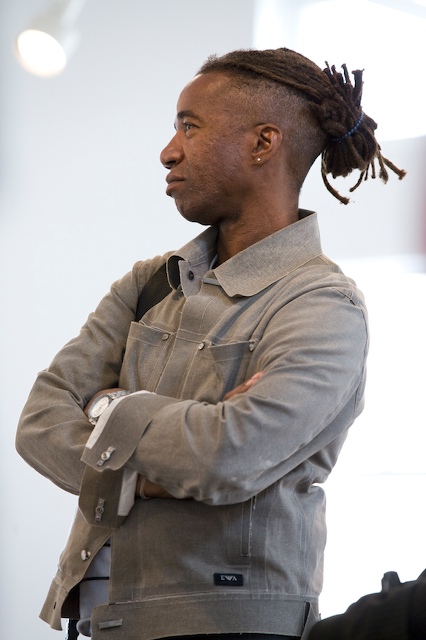

After the exhibition tours the Close Encounters group returned back to Ruatepūpuke II for a hui inside the wharenui. The hui was started with a talk about the history and cultural significance of Ruatepūpuke II lead by Hakiwai, Terrell and Wharehinga. The talk was followed by individual mihi from everyone in the group. This provided the opportunity for all those involved to both think about their own and everyone else’s complex cultural belonging.

Later that evening, the AIC and their community held a large powwow. The event was an exciting cultural experience for everyone. It included a large meal followed by traditional drumming and dancing in which everyone was invited to participate.

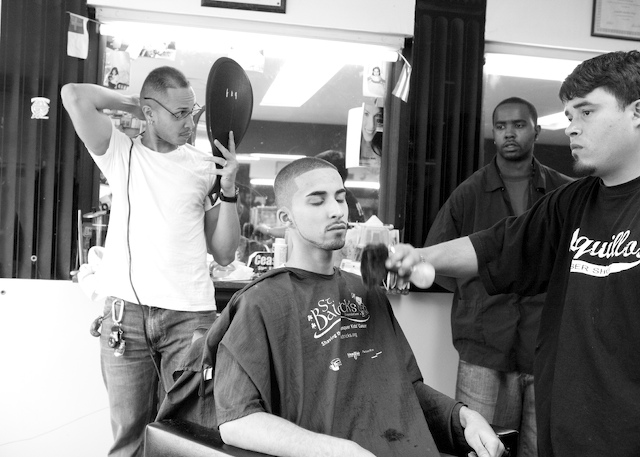

The following day, we divided the artists and other hui participants up into two groups for a tour of Chicago. We sent one driving North and the other driving South. The tours visited ten large and small community groups and organisations. Ranging from non-traditional urban groups such as the skateboard and parkour communities to highly organised trusts born from a need to formally function in a social welfare capacity. These included, the Cambodian Center, set up to council and re-educate Cambodian refugees, and the Center on Halsted, which is a LGBTQ community centre that also services all other walks of life.

When the groups returned that evening the north group was buzzing with utopian aspirations. In contrast, the south group returned totally depressed, as their whole day had involved driving through some of Chicago’s poorest ghettos. However, it is precisely these positive and negative community encounters that proved vital in inspiring each artist’s work and helping them to challenge conventional notions of community.

Due to the in-depth nature of the projects, I will focus on just a two in detail including Signs and wonders shall appear (2010) by Maddie Leach and a social intervention by Tania Bruguera.[5] These two artworks proposed different models of how conceptual artworks can engage with community and set specific challenges to the curatorial parameters of Close Encounters as a whole.

___________________

Beaver Island, on a frosty morning in early October 2010. Maddie Leach concluded two years research by picking apples in the Beaver Archipelago – a small group of islands in northern Lake Michigan. The small remote islands have a combined population of 600 and a peculiar abundance of wild apple trees that were planted by a clandestine religious community called the House of David who retreated there in the late nineteenth century. These apple varieties are now unique to the islands. Some trees are well over one hundred years old.

Leach collaborated with the people of Beaver Island to locate the trees – as many are kept secret or require local knowledge to find them. To do so, she organised a research trip to get to know the islands and the community. Leach instantly became accepted and before she knew it she was invited on hunting trips and was talk of the town. To locate the trees Leach also published this advertisement in the local newspaper The Beaver Beacon.

A year later, Leach returned to the islands and with the help of some locals she collected several crates of wild apples. In Chicago, Leach shared the island’s unique produce by a call to interested people to receive a gift of Beaver Island apples. A large hand painted sign on the HPAC’s garage door facade announced the arrival of apples from the island and directed local passers-by to a nearby marina where they could receive them. Visitors were given two pounds of apples – the perfect amount for one apple pie. Through this gift exchange Maddie was interested to discover what might represent Beaver Island, as a New Zealander something that represents ‘islandness’, and in turn what could be exchanged with communities in Chicago.

One of the outcomes of this transaction – was good ol’ American apple pie. In an associated event at a local organic farmers market, four different apple pies were baked for taste testing each one containing a different variety of Beaver Island apple. Apples and apple pie are a national obsession in the United States so the offer of free organic heirloom apples caused much excitement and conversation about the island, the people that live there and the history of the apples. For the Beaver Islanders, it drew attention to the wealth of their natural resource and inspired much entrepreneurial spirit about how they could capitalise on their unique apples and recognise the cultural value of their local history.[6]

For the south side of Chicago, the project had a whole different significance because it is in this area that food deserts exist. Food deserts are areas where healthy affordable food is difficult to obtain. On the south side, Supermarket chains refuse to set up stores for fear of crime, resulting in most people buying junk food from convenience stores. So to a poor and also strongly religious population who live in the reality of food deserts, the project Signs and wonders shall appear made a generous and poignant statement.

However, while these were some of the most direct outcomes of the project it is just one perspective of how the project could be framed. For example, despite the hundreds of people that engaged with the project on some level Leach insists that the project only reached an audience or community of two people. The reason for this is because there were only two people who read the painted sign and followed the instructions to find the apples at the marina. For Leach, the ideal community she was interested in engaging with was those that took the time to notice and took value in the gift on offer.

Most other people either found out through word of mouth or by chance. Throughout the project, Leach resisted the use of mass communication to incite the interest of the local community. There was no social media announcements and no flyers printed, only a hand painted sign on the HPAC garage door that you would have to walk past to read. This, among other aspects of the project, put Leach’s work in a risky position of possibly not connecting with anyone. Throughout the development of the project this risk of ‘perceived failure’ was always an intentional possibility. As an individual and an artist foreign to the location, Leach was conscious of not assuming her right to identify or speak for a particular community or to coerce involvement of people to complete the work.

Her aim was to simply provide the conceptual possibility of exchange between two places. This act, of creating the parameters of possibility, makes Signs and Wonders Shall Appear a compelling example of how artists might invite community to participate on their own terms. From a curatorial perspective, it raises the question of quality of experience versus easily consumed ideas that draw in the masses – a tactic often employed in ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions. This is an especially difficult risk to entertain since the success of most publically funded museums and galleries are assessed by visitor numbers alone usually by city governments and funders.

___________________

Chicago, 2 p.m. on Sunday, 8 November 2009. It was the last thing anyone expected to happen at a HPAC exhibition opening. For no good reason, or so it seemed, people were asked to queue single file and subjected to stern questioning before being granted entry. Unbeknown to these faithful art lovers, their bemusement, frustration or unfazed acceptance of authority were actually contributing to a performance by Cuban artist Tania Bruguera. A performance designed to simulate how bureaucratic power interferes with societal belonging.

Occupying a desk at the main entrance sat Cecilia Vargas the lead performer who acted as the gatekeeper. There were also two undercover performers who waited in line and initiated casual conversation designed to incite rebellion. Dressed in an authoritative fashion wearing a black shirt, skirt and leather boots Vargas improvised her authority on incoming visitors. Acting under instructions from Bruguera, Vargas used suggestive phrases that did not order people what to do but rather compellingly suggested their submission. In addition, she used body language and an authoritative voice as codes for establishing a power relationship between her and gallery visitors. Using visual markers such as a strip of black carpet Vargas also convinced people to orderly line up single file for questioning. She continued to ask each person statistical information such as name, age, occupation, why were they attending the exhibition opening and what were their expectations. On occasion, when there was not a satisfactory reply, someone would be sent to the back of the queue to consider who they are and why they were visiting.

The performance lasted for about an hour during which the line would naturally form, dissipate and then grow again. The prescience of the line was like a living and constantly changing object. The other interesting aspect was how it worked contrary to the community philosophy and architecture of the HPAC. Being a contemporary art centre that functions as an inclusive hub for a range of diverse community groups, it was a great surprise to many that they would have to wait and be interrogated. The HPAC is also an open and welcoming institution architecturally since it has many entries into the building rather than just one.

Therefore, those who were familiar with the building, or those smart and cunning enough, could exercise their free will to find an alternative entrance. While others, by default, chose to be complaint and waited quietly in line. Some well-known patrons and curators in the Chicago art community who felt a sense of entitlement and attempted to directly bypass the line. When asked to queue up they stated their importance and refused to comply. There were also a few people that quickly guessed that it was some sort of performance, or who learned once gaining entry, and proceeded to participate in the line numerous times.

The performance intervened surreptitiously into the social convention of an exhibition opening. It occurred in such a way that most people were not aware of it being a performance. This social intervention was significant to how the majority of people are often willing relinquish their personal information to participate in society. It also proved that it is often small groups of people that question requests and who take the initiative to collectively or individually subvert such assumed authority.

As a Cuban artist, Bruguera knows all too well how structures of power can be enacted since in Cuba it is very hard to intervene and disturb social conventions like this without getting in trouble with the authorities. However, in the context of the United States Bruguera believes there is an even stronger need to intervene in such a furtive manner. She argues that “society should be about freedom, but not in the sense that it is used in the United States where freedom is used in a very antidemocratic and contradictory way”.[7] Rather she wants people to be thinking actively:

Society should be about a group of people getting together to do something, and part of coming together is to think . . . people are not thinking, they are just doing and they let someone else think for them.[8]

The curatorial methodology of Close Encounters posed significant challenges to conventional institutional practices by initiating artistic research, allowing artists to develop their projects on their own timeframe, developing curatorial frameworks and artworks in tandem. The results of this methodology are clearly apparent within the freedom and experimentation of Leach’s and Bruguera’s works.

[1] Doreen Massey, “Some Times of Space,” in Time: Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art Series (London: Whitechapel, 2003), 117–118.

[2] Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community, 3rd edition (New York : Berkeley, Calif.: Marlowe & Company, 1999).

[3] Mary Jane Jacob, “Outside the Loop,” in Culture in Action (Seattle: Bay Press, 1995); Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship; Doherty, “Art in the Life of the City: London Stories.”

[4] Personal communication.

[5] Tania Bruguera did not give this artwork a title.

[6] Maddie Leach, “Art, Fruit and Confrontation,” Arts on Sunday (Radio New Zealand, November 7, 2010), http://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/artsonsunday/audio/2429856/art,-fruit,-and-confrontation.

[7] Tania Bruguera, In Line for Close Encounters, interview by Bruce E. Phillips, 2009, http://www.taniabruguera.com/cms/248-0-In+Line+for+Close+Encounters.htm.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Möntmann, “Curating with Institutional ’Visions: A Roundtable Talk,” 2006.

[BEP1]cut?