Farewell is the song Time sings

Published in:

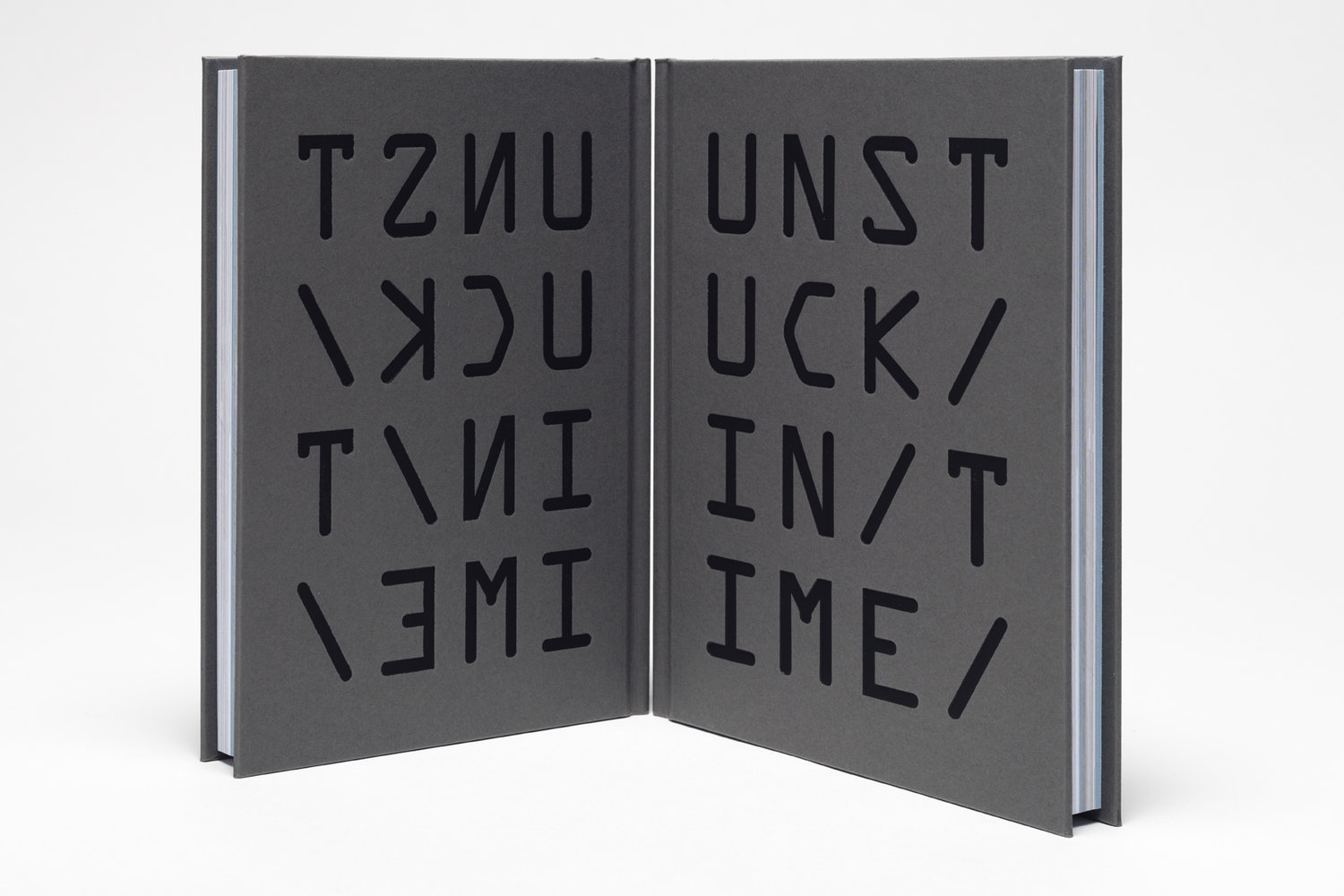

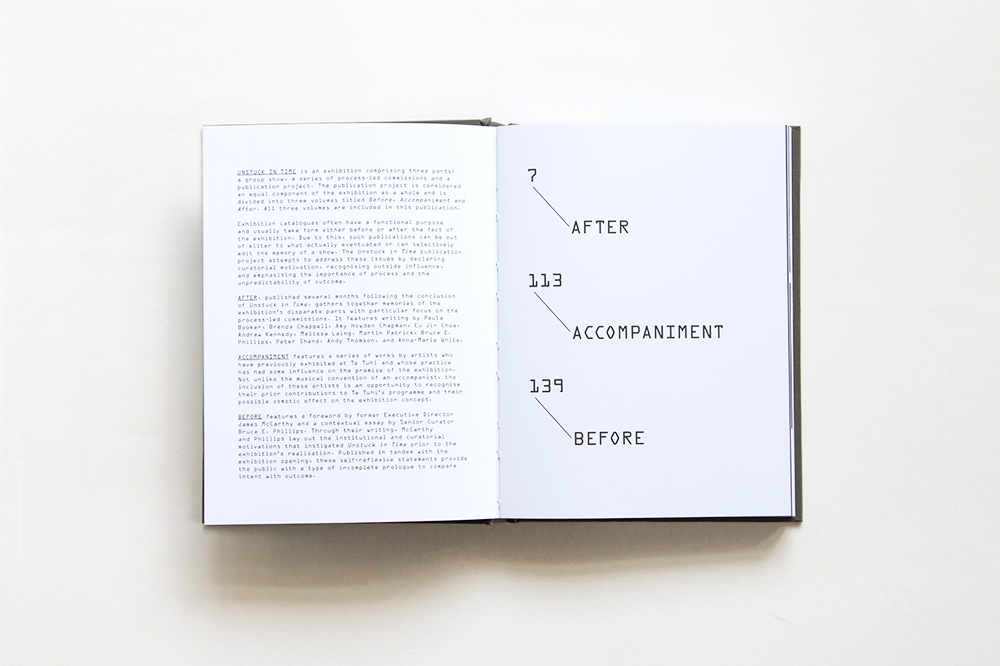

Unstuck in Time

Edited by Rebecca Lal

Te Tuhi, Auckland

2015

ISBN: 978-0-908995-52-3

Download the ebook

In early nineteenth century Britain, factory workers protested against long hours by smashing the clocks that presided over factory gates.[1] Almost 200 years later the clock’s dominance is so amalgamated to daily life that it continues to tick relatively unchallenged in the shadow of our political subconscious. For, what was invented to be merely the unit marker of time has now become the physical embodiment of ‘the time’. Consequently, this deeply embedded social norm has fundamentally influenced how we as a species have occupied the planet and related to each other since the industrial revolution. Now with the reality of global warming we find ourselves at the eve of a grave tipping point in the earth’s history and it seems even more important than ever that the perception of time should be questioned if not radically revised.

Admittedly, to revolutionise our dependence on mechanised time would require a significant upheaval – possibly more challenging than the transition from fossil fuel dependence. The other great difficulty is that time is a slippery and complex dimension for us to individually grasp let alone collectively consider substitutes. Perhaps for this very reason, creative practitioners have been greatly interested in the problematic illusiveness of time and as such have played an important role throughout history in mediating our comprehension of it.

The driving motivation behind Unstuck in Time was to engage in this history and where possible to provide the artists with the opportunity to respond to the urgent concerns in the present. In researching for this exhibition, three key aspects of time became apparent to me: the creation of mechanised time, the evidence of deep time, and the experience of time as duration. From these few subjects vast constellations of knowledge and histories branch out and intersect. In this essay, I will seek to unravel a small portion of this rich context in relation to some of the selected artists’ work.

I admit that this essay is written ahead of time and I am aware that it is greatly assuming to do so when the exhibition has yet to take place. To use the words of art critic Terry Smith: ‘no matter how well the curator knows the work . . . when writing the catalogue the curator can state only a belief about the subject of the exhibition’.[2] Thus, I hope the next few pages read not like a definitive script but rather a collection of beliefs unstuck between moments of thinking and doing.

I should disclaim any authority on the topic of time or any great skill to write about it. The purpose of this writing is simply an exercise in curatorial contextualisation – hopefully for the benefit of the art and those who will experience the exhibition in its multiple formats. Written slowly and infrequently over six months or more, it has been pieced together from old notes and is greatly influenced by science fiction as a portent lens to see the present.

__________________

Year 100 AF

Auckland, 11 a.m. on Monday, 2 December 2013. I am clicking through a bunch of lapsed reminders in my digital calendar that I need to catch up on before the year runs out. Number-one priority is to contact a historic preservation trust who have promised us the use of a protected 1930s bach on Rangitoto Island for an artists field trip we are organising in mid-January. Everything seems to be falling in place but with the pre-Christmas rush escalating around me I can’t help but become nervous that it might all fall through. Let’s face it, it’s a poor time of year to contact people. Yet despite this slow-burning anxiety, when a low priority reminder catches my eye, the allure of procrastination gets the better of me – just yesterday was the centenary anniversary of Henry Ford’s production line.

In the dystopian future of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, this year would be the first century of ‘our Ford’: Year 100 AF (After Ford). By marking the year zero as 1 December 1913, the day Ford revolutionised the world with mass production, Orwell marks the date when issues of labour and class challenged longstanding values of humanity. For us today, who live beyond Huxley’s fictional future, the birth of Fordism bears a whole different significance as the day the world started to speed up exponentially. The rapid change that Fordism would create was impossible to fathom. As Ford’s assembly line accelerated production of one Model T Ford every twelve hours to one every two hours he famously proclaimed, ‘I will build a motor car for the great multitude.’[3] The fact that everyone would have access to the significant innovation of mobility did not raise alarm bells to people then as it does now. The main concern of the time was the dehumanisation of the labour force of which Ford’s assembly line would come under scrutiny because of the management philosophy of his cohort Frederick Taylor.

Taylor’s approach of Scientific Management sought to apply the systematic study of tasks which led to observation and direction-based management of each worker in the line. At the heart of his methodology was a determination to break the back of workers’ solidarity. Taylor believed that such social collectively bred habitualised laziness to the degree that men became ‘so stupid and so phlegmatic that he more nearly resembles in his mental make-up the ox than any other type’.[4] In place of the traditional worker-to-worker training, Taylor instituted micro-management undertaken by appointed supervisors who would observe their subordinates, stop-watch in hand, to ensure that methodical precision and speed in task was achieved.[5] In this sense, the control of bodies and their movement in time and space became the ultimate picture of productivity.

The production-line time flow could only be enforced via observation and in many ways worker loyalty-to-task is still important today with behaviour kept in check via CCTV surveillance – – a future not too dissimilar to George Orwell’s ‘Big Brother’, the omnipresent Thought Police in his novel Nineteen Eighty Fou. This heavy-handed control of life was expounded by the novel’s antagonist O’Brien:

Obedience is not enough. Unless he is suffering, how can you be sure that he is obeying your will and not his own? Power is in inflicting pain and humiliation. Power is in tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together again in new shapes of your own choosing . . . If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – for ever . . . We control life, Winston, at all its levels. You are imagining that there is something called human nature which will be outraged by what we do and will turn against us. But we create human nature. Men are infinitely malleable.[6]

However, what Taylor or Orwell did not concieve of was the potential for observational media and method to be used in a subversive capacity in support of the working class, as it would later in the documentary work of photographers such as Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. Drawing on this legacy later in the 1970s, Darcy Lange developed his interest in the representation of labour through moving footage. Lange’s documentation sought to ‘re-incorporate the somatic dimension of production’ but also the individual suffering of monotonous labour interned by the spatio-temporal control of the body to perform factory floor tasks.[7] When making A documentation of Bradford working life (1974), a series of video works, Lange recognised the particular space-time influence on the factory workers he was filming:

With the tightening of the video camera style and with the observation centred around that one person, various qualities came forward. The studies became performance analysis, they searched the monotony of the work, they questioned the work load and the suffering due to the work, and they became a kind of uncomplimentary social realism.[8]

Darcy Lange, A documentation of Bradford working life, 1974

(video still) courtesy of the Lange family; the Govettt-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth; The New Zealand Film Archive, Wellington. Special thanks to Mercedes Vicente and Kelly McCosh.

It is also important to note that the early 1970s, during which Lange was making these works, saw the birth of globalisation. In this new post-Fordist period, production would yet again accelerate exponentially but this time from being outsourced to the so-called ‘third’ or ‘developing’ world where human life is more plentiful and cheaply harnessed – more so than that of the migrant workers who were employed in the old industrial centres such as Lange’s Bradford – and which makes up a workforce that labours while the Western world sleeps. In the following decades of global capitalism much would be squandered to fuel the insatiable desires of first-world consumerism. Fast-forward to 2008 and we find the end game of this financial system with the worst economic crisis since the great depression of the 1930s.

As the chain reaction of defaulted loans trickled around the world, the time flow of modernity became unstuck with the only forward movement measured in levels of liquidation and decay as banks vanished and brand-new housing developments became ghost towns. This is the geo-economic circumstance in which Nicolas Kozakis and Raoul Vaneigem’s A moment of eternity in the passage of time is situated.

Kozakis’ black and white video footage depicts a lone migrant worker slowly constructing a traditional stone house on Mount Athos, a remote peninsula in northern Greece reserved for Orthodox monasteries and restricted to male visitors only.[9] The man’s slow, pensive and hand-made work is symbolic of a pre-industrial form of commodity where, via a Marxist understanding, the use-value and exchange-value is tangible to the task achieved – rather than created by a social power structure. Vaneigem’s text, overlaid on the man’s labour, reflects on the state of the world in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis and the potential for a future more ethically in tune with people and the earth. His subtitled poetry gives much weight to the thoughts of economic deceleration and the politics of labour. One passage reads:

Happy is he who discovers the slowness of life

As [a] world frenzied by power and money

Is collapsing around him

We do not fully discern how well we have won

The silent solidarity

Of stones and beasts[10]

As if acting out Vaneigem’s verse, the unnamed worker pauses in between tasks to take contemplative cigarette breaks by the sea. The worker’s gaze out to the Mediterranean horizon on this secluded sacred site silently evokes the historic legacy of our current concept of linear time. In Greek mythology the flow of time was encapsulated in the pseudo-geographical deity Oceanus, an infinite boundless river that encircled the whole world and from which life and all rivers flow.[11] However, the ancient Greeks also had other divinities who embodied properties of time’s temporality that were in contention to the eternal waters of Oceanus. Of these gods the most influential on us today is Chronos. It is from Chronos that we begat the notion of time being a divisible forward motion independent of humankind.[12]

Nicolas Kozakis & Raoul Vaneigem, A moment of eternity in the passage of time, 2012

(video still) digital video, 5 minutes courtesy of the artists

From this theoretical beginning a succession of philosophers, scientists, mathematicians and inventors throughout history have sought to separate time as a distinct calculable entity. As with all great innovations, there have been many mathematical divisions and technological permutations throughout history. If we leap past sundials and the many peculiar experiments of recording time we will arrive at the mathematical conceptualisation of the second in the fourteenth century. One more stride further into the eighteenth century and the second is finally accommodated through advances in clock technology. Come the nineteenth century global timekeeping had become of pressing international concern, well at least among those in the West. In 1884 at a conference held in Washington DC, delegates from 25 nations came to the arbitrary resolution to establish the Greenwich Meridian as the world’s time standard. Then, at 10 a.m. on Tuesday, 1 July 1913, the first time signal was transmitted from the Eiffel Tower, more efficiently synchronising Greenwich Mean Time across the globe. Coupled with Ford’s production line this event made 1913 a year of irrevocable change.

Thirty-one years and two world wars later, George Woodcock, an anarchist philosopher and good friend of George Orwell’s, fervently articulated the effect of time’s dominance in his 1944 essay The Tyranny of the Clock. Woodcock’s writing is full of sweeping statements against ‘the tyranny of abstractions’ as a self-destructive mechanism.[13] He demonises the clock and considers it an unnatural abomination to fear and loathe:

without some means of exact time keeping, industrial capitalism could never have developed and could not continue to exploit the workers . . . Time as duration became disregarded, and men began to talk and think always in ‘lengths’ of time, just as if they were talking in lengths of calico . . . men actually became like clocks . . . they became the servant of the concept of time which they themselves have made, and are held in fear, like Frankenstein by his own monster.[14]

I picture my near-future self sitting in Te Tuhi’s gallery space watching the tick of Toril Johannessen’s very beautiful Dutch train-station clock and I wonder if Woodcock’s dread of the clock still holds today. The circular analogue dial now seems so harmless and nostalgic. It is more and more common for clocks to be used as a feature in interior decor or, in the case of watches, as expensive status symbols glistening on the wrists of celebrities and high-powered executives. Or so we are lead to believe through classy advertisements featuring famous Hollywood actors looking calm, casual and sophisticated wearing a classic timepiece. Like many others today, my main source of time comes from a smartphone which is synched via the internet to change as I pass through different time zones. Although, these ‘smart’ devices want more of us than merely sharing the time. Their slumbering void-like obsidian screens burn psychic holes in our pockets – they alert us with chimes and vibrations, begging to be illuminated and connected. This technology modifies us not by organising our movement like that of the clock but by being cognitively, physically and socially part of us. Thus, the topical monster of our present is not necessarily the omnipresence of mechanical time but rather the smartphone cyborg or the social-media Narcissus.

Perhaps this is why Johannessen decided to fuse the analogue with the digital in her work Mean Time. In this work, Johannessen has re-geared the train-station clock, a classic signifier of time and being on time, to run by the pace of real-time internet activity. The more bits and bytes that are processed and consumed around the world the faster the hands rotate. By amalgamating these histories of technological innovation Johannessen’s work tests our psychological association of what time currently means to us.

Toril Johannessen, Mean Time, 2011

Dutch train station clock re-programmed so that the pace is contingent on the current global internet activity.

courtesy of the artist

photo by Ian Powell

Johannessen’s work is also significant because it references the close connection of time with communication. In her popular book Pip Pip: A sideways look at time Jay Griffiths builds the link between the advances in mechanical time and the rapid acceleration of connectivity in the early twentieth century. In particular Griffiths points to a specific moment: North Atlantic Ocean, midnight on 14 April 1912, when the distress signal was sent from the sinking Titanic:[15]

The news flashed around the world via the telegraph. People referred to ‘a new sense of world unity’ and what is now called the creation of the ‘global present’ . . . The media (newspapers, telephones, radio as well as the telegraph) buzzed with the news, blaming the tragedy, incidentally, on an obsession with time-keeping over safety . . . But the media itself was implicated not only in the creation of this global present but also in the portrayal of time . . . The association between the media and present-time is so deep that almost every part of the media is named with the time referent; Paris-Midi itself, Time Magazine, the New York Times, Die Zeit (the Time), Asahi Shimbun (the Morning Sun newspaper in Japan) . . . The new global media technology, because of its mechanics, favoured the short over the long. Information became broken and fragmented rather than continuous.[16]

With advancements in technology notions of the ‘global present’ would come to be surpassed by the virtual experience of so-called ‘real-time’ as used in film narrative via the long take and even more apparent with live radio and television broadcasts. With the advent of internet-based social networking via websites such as Twitter and Facebook the live broadcast has been surpassed by the easily accessible instant message which has empowered notions of global democracy and collectivity. So powerful is this readily available form of instant communication that it has proven to be a political game changer and has been quickly taken up as a tool for local and global activism especially during the Arab Spring and Occupy Movement in 2011. Time, and especially understandings of real-time, is now associated with the rate at which we can communicate, and has indeed mediated that communication and our socio-political reality. Likewise, the mean of our time via the internet, like Johannessen’s clock, is measured by the speed of connection and the velocity determined by the emergent network of individuals clicking, posting, downloading, sharing and trading.

_____________________

Descent into deep time

At home, 7:12 a.m. on Thursday, 27 March 2014. Bleary-eyed and sipping on a ritualistic cup of black coffee, I read a sobering news article about a major report just published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.[17] The report states with 95% certainty that humans are responsible for global warming since the 1950s.[18] The report also forecasts the ecological and humanitarian impact this will have over the next 100 years. Along with rising temperatures the acidic level of the ocean will rise, agriculture will be hit by a decrease of up to 2% on global crop yields and millions of people living in coastal areas will be affected by flooding and displacement.[19] It is indeed a grim forecast of the future. As I read urgency is kindled but suddenly snuffed out in realising that change, given the amount necessary, is most probably economically and politically impossible without significant overhaul and sacrifice by us all. This lingering defeat is reinforced a few days later when I read a news article about the response to this report from New Zealand Climate Change Minster Tim Groser who says: ‘We’re not playing God on this. That natural process will determine what happens to adaptation of human beings and other mammals and species.’[20] While Groser’s comment is revealing of the government’s true motivation for inaction, it also raises philosophical questions regarding what this future of human adaption might look like if left unchallenged.

Science fiction has given us a few such visions of where human adaption may take us. Writer J.G. Ballard once said that science fiction can act as ‘a sort of early warning system’ by analysing ‘what is going on around us, and whether we are very different people from the civilised human beings we imagine ourselves to be’.[21] This is especially true of his prescient 1962 novel The Drowned World in which he reminds us of how preconceptions of the individual and humanity are really a ‘late artefact’ in the evolution of Homo sapiens and can be ‘dismantled overnight’.[22] Writing decades before man-made climate change would be verified, Ballard conceived of a flooded earth due to a sudden increase in solar radiation rising global temperatures over a 60–70 year period. With the polar ice caps and glaciers melted the sea floods once temperate regions of the earth, reducing cities to strange aquatic environments with high-rise buildings poking out of the water like forests of ‘giant ghosts’.[23]

In this hothouse world the growth of flora and fauna has rapidly accelerated to the degree that rampant mutations of gigantism have produced vast swamp jungles populated by colossal reptilians and insects as if it were a second Triassic age. Such extreme adaption has occurred in all species apart from humans who have chosen to inhabit the slightly cooler regions in the far north or south. Musing on this ‘geophysical upheaval’, Ballard’s protagonist Kerans considers the devolving state of humankind:

Kerans sometimes reminded himself, the genealogical tree of mankind was systematically pruning itself, apparently moving backwards in time, and a point might ultimately be reached where a second Adam and Eve found themselves alone in a new Eden.[24]

Kerans’ narrative is foreshadowed by the increasing frequency of intense dreams that unearth primeval memories lodged deep within his subconscious: ‘Kerans felt beating within him like his own pulse, the powerful mesmeric pull of the baying reptiles, and stepped into the lake, whose waters now seemed an extension of his own bloodstream.’[25] The story ends with Kerans giving into his delirium by going AWOL in the sprawling aquatic jungle on an illogical ‘neuronic odyssey’.[26]

In 1935 H.G. Wells also considered a not too dissimilar future of back-sliding human adaption in his novel The Time Machine. The story is narrated by a Victorian scientist and chronicles his odd voyage across time and space upon which he encounters two evolved species of Homo sapien descent. While a great part of the story’s drama takes place in the company of these questionable humanoids, the time traveller eagerly wishes to escape their backwards existence. He expounds:

I grieved to think how brief the dream of the human intellect had been. It had committed suicide . . . And a great quiet had followed. It is a law of nature we overlook, that intellectual versatility is the compensation for change, danger and trouble. An animal perfectly in harmony with its environment is a perfect mechanism. Nature never appeals to intelligence . . . where there is no change and no need of change.[27]

Both Ballard’s and Wells’ futures brew an eerie resonance of Groser’s statement and provoke a clear picture what of human adaption may look like in the face of climate change. In The Drowned World rational logic is forced to reckon with an undeniable truth that humans are indeed not separate from nature but part of it and will someday return to the primeval mire. The uncomfortable reality that faces us is that, unlike Ballard’s future where the earth changes of its own cosmic accord, we are causing the change in the earth’s climate with every ounce of fossil fuel we burn. Coupled with Wells’ allegory that by striving for this comfortable way of life in the present, we are sacrificing any evolutionary edge that we might have with human intelligence and stand to lose any sense of ethical humanity.

This situation presents two clear options regarding the potential future of humankind. Either, we live in comfortable ignorance by taking full advantage of present recourses and ‘let the chips fall where they may’ for our future descendants. Or, strive to avoid our fatal destiny by changing how we live. Above all, what is greatly needed is a time perspective beyond the rational enlightenment thought that human intellect is part of evolutionary progress moving forward in a linear chain of improvement. To truly reconsider this time paradigm it is imperative that we undertake a 'descent into deep time'. [28] If we return to Wells’ time traveller we will find him speeding past the fatal end of the human family to witness vast passages of time empty of any human presence:

Slower and slower went the circling hands until the thousands one seemed motionless and the daily one was no longer a mere mist upon its scale[29] . . . All the sounds of man, the bleating of sheep, the cries of birds, the hum of insects, the stir that makes the background of our lives – all that was over.[30]

Here the time traveller is stumbling across ‘deep time’ and learns the pages of the earth’s history of which humans occupy merely a minuscule part. Deep time is a term used by geologists to describe units of time in the measure of billions, a number so vastly beyond easy human comprehension that it warranted such a poetic phrase. Biological life sneaks into this geological deep time through evidence of fossils from which the evolution of species has been pieced together. To enable this perspective of the earth’s epic timescale we need not appeal to the fanciful fiction of possible futures. The evidence of deep time is clearly visible in the present by attuning oneself to the immense archives in storage below our feet.

This attempt at tuning into the perspective of deep time as a counterpoint to human existence is a driving motivation behind Medium Earth by The Otolith Group. Observing the geography of California and in particular the San Andreas fault, the work begins by following the fault lines that have caused crazed fractures through human infrastructure such as buildings and motorways. By tracing the trail of these fissures in tarmac and concrete, the camera is led inland to discover more epic tectonic lines that take the form of vast mountain ranges and crevices cutting through desert plains. Interludes of ambiguous poetry allude to evidence of time locked still in inert strata and conversely the earth’s continual fluid movement due to its volatile liquid core. The poet’s voice educates us:

Blind idiot gods in ancient ocean basins igniting their latent energy of thermo nuclear devices. The window keeps moving us out catching us in its timeline, it makes mothers of us. In a 72 hour timeline we are 3 million years old reporting back from waste lots of porous rock boulders touching at angles of repose . . . We are sinking below its crust into plates colliding forming new mountains . . . We are gasses ignited by the earth’s nocturnal core its seething reservoir, hotter than the surface of the sun. 3,000 clicks beyond the cold crust the semi fluid metallic ocean the geo-cosmic motor running the plate tectonic machinery . . .[31]

Throughout the work, there is also a suggested longing towards attaining prediction or a premonition of future seismic activity. In a lecture performance relating to Medium Earth, The Otolith Group discussed how new technologies have greatly improved calculation of seismic events. As a result the science has become less about prediction and more about understanding variability in greater detail. However, the inability of scientists to magically give us absolute certainty inevitably creates unease for many as it speaks bluntly about our vulnerability living upon the earth’s crust. This cold serving of fact results in a social and psychological dilemma. From such unease grows an overwhelming desire for the sanctuary of absolute answers, and from this, beliefs are born that may have some origin in proven science but can become blindly exaggerated far beyond reason. This is the creation of pseudoscience and if such beliefs gain popularity they can have serious ethical and political implications. The pseudoscience of eugenics is such a historic precedent. By siphoning its legitimacy from the science of evolution, eugenics influenced a ‘biologisiation of society with fantasies of social Darwinism’[32] leading to horrific consequences during the twentieth century. In light of this, what will the sociological effects of this unease be in an age of advanced geological science?[33]

The Otolith Group, Medium Earth, 2013

(video still) HD video, 41 minutes

commissioned by RedCat, Los Angeles

courtesy of the artists and LUX, London

To investigate the possibilities of premonition over prediction, The Otolith Group researched people who claimed to have extrasensory experiences of seismic events. In such instances the body is said to become a medium through which prophetic intimations of the earth’s movements can be physically perceived. Medium Earth was therefore an attempt at attaining a sort of ‘geological consciousness’ that muddles scientific investigation with claimed psychic responses to the earth’s seismic activity.

For better or worse, such an attempt at an extraordinary deep time perception amplifies the awareness of humankind’s miniscule existence on the earth’s timeline. Overall, our reluctance in reconciling such ultimate realities will decide the evolutionary path in which the species will tread – whether that be the loss of infrastructure because we are willingly blind to the geographic reality in which we place our cities or that of global warming when we irrevocably tip the environment’s balance.

__________________

Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time

Chicago, 7:30 a.m. on Thursday, 12 April 2007. I wake to the comforting smell of filtered black coffee that Chuck Thurow, my host and now good friend, brews daily. Grasping only a thread of consciousness, I rise out of bed forgetting that resting on my chest is a copy of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five.[34] I had stayed up late to read the concluding chapter and had promptly fallen asleep during the last few words. Recovering the book from the floor I glance out the window at a still spring morning and a bright-red singing cardinal perched on top of a neighbouring roof. This is the second of what will be many trips to Chicago. Chuck has invited me back on this occasion to develop a project with him, the idea of which is still very unresolved. There is something special about getting to know someone else’s morning routine and I have grown to be fond of Chuck’s. An early riser who is known for a brisk walk first thing or a swim in Lake Michigan he will return home to his coffee and two newspapers the Chicago Tribune and the New York Times. I especially enjoy reading a newspaper in the mornings and think it a privilege to be absorbing journalism so connected to world events as opposed to the parochial news we receive back home. This particular morning Chuck is still reading the Times so I make do with the Tribune and am immediately struck by a small column headline: ‘Kurt Vonnegut, known for classic novels, dies’.[35]

I am not really a believer in fate but I am greatly unnerved by moments of apparent synchronicity. Without being superstitious, I do think that such occurrences should not be simply shrugged off as coincidence but rather considered as poignant moments to reflect upon. There is no rational basis for this of course, but humans, I have found, are not rational creatures. We absolutely require at least a light touch of the mystic in order to live with uncomfortable truths – whether that be beliefs, stories, or ideologies. In writing on the work of artist Olarfur Eliasson geographer Doreen Massey eloquently explains the significance and phenomenon of such collapsing histories that occur in our daily movements:

Imagine a journey. It does not have to be an epic one . . . simply from ‘here’ to ‘there’ . . . this movement of yours is not just spatial; it’s also temporal . . . Your arrival . . . when you step off the train . . . is a meeting-up of trajectories as you entangle yourself in stories that began before you arrived. This is not the arrival of an active voyager in an awaiting passive destination but an intertwining of ongoing trajectories from which something new might emerge. Movement, encounter and the making of relationships take time . . . An encounter is always with something ‘on the move’ . . . If movement is reality itself then what we think of as space is a cut through all those trajectories; a simultaneity of unfinished stories.[36]

Massey’s so-called trajectories of multiple pasts run directly in the face of the imperialist notion of unitary and linear time. It is a perception of time that is inexplicably wedded to place and how we physically, politically and psychically inhabit a movement. This is an all too human perception. As philosopher Henri Bergson surmised through his theory of multiplicity, humans are first cognisant of time as duration rather than singular abstract units. He adds that such rational compartmentalisation becomes merely ‘symbolical substitutes’ for ‘all unity is the unity of a simple act of the mind’.[37]

This notion has a strong reverberation throughout the history of art. For, to experience time in culture is often to be lost-in or aware of one’s duration of being rather than consciously calculating units. Hence, there are numerous cultural perspectives of time that indeed do not separate it in a singular unitary sense but instead understand it philosophically in relation to a complex web of associations. These associations include, but are by no means limited to, ancestry, deity, mythologies of all sorts, and, observable periodic events such as the seasons, astronomical movements, solar and lunar phases. To this list we should also add Massey’s psycho-geographic understanding of movement and place: ‘For the world is specific, and structured by inequalities. It matters who moves and how you move.’[38]

An artist who knows all too well the reality of time as duration and the politics of movement is Tehching Hsieh. At 2 p.m. on 26 September 1981, Hsieh stepped out of his humble Manhattan apartment after signing the statement: ‘I shall stay OUTDOORS for one year . . . I shall not go into a building, subway, train, car, airplane, ship, cave, tent.’[39] In leaving his home, Hsieh opted out of a ‘socially acceptable’ mode of being and put himself at the mercy of life on the streets and that of New York’s extreme weather.

Tehching Hsieh, One Year Performance 1981-1982,

(26 September 1981-26 September 1982)

poster, statement, map, photographs and video, 32 min

courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

photo by Sam Hartnett

Above all, Hsieh placed himself in another frame of time, one that was fundamentally outside of the economic flow and function of the city. In simply being aside of the business of ‘life’ Hsieh, through his humility, gained a perspective on surviving and also what it means to resist the rhythm of collective belonging in order to exercise individual freedom. With the restraints of work life and citizenship halted it seems time is expanded to include the ability to ruminate, wonder and be at pace with one’s own time. In Hsieh’s comprehensive publication Out of Now, Adrian Heathfield writes that this was all the more apparent in New York during this time:

Hseih’s walk in the early eighties takes place in a time of rapid capitalization and privatization of public space. Within such spaces normative imperatives grasp human action. Travel in these places becomes functional and instrumental: it is geared toward a productive and ever more economic use of time . . . In a movement culture orientated towards acceleration he proposes stalling, deferral and misuse of time as a means to access alternate realities.[40]

Hsieh’s movements were further politicised as he was not recognised as a legal citizen of the United States and as such he risked ‘far more than the discovery of his inauthenticity as a street inhabitant’.[41] The reality of this risk came close in May 1982 when he was arrested and dragged into a police station, breaking his roofless covenant and putting him in serious threat of legal discovery. He was arrested due to an alleged altercation with a homeless man in which Hsieh brandished a nunchaku in self-defence.[42] Thankfully he was released with no questions about his legal status.

Hsieh’s corporeal duration, therefore, was framed in relation to forms of power infrastructure: the architecture and Cartesian grid of Manhattan, social conditioning of the time, legal governance and police enforcement in one of the world’s most powerful cities. Hsieh charted these relationships as he experienced them in red ink on photocopied maps of Manhattan with indications of places to eat, sleep, wash and defecate. Viewed now in the gallery space, these notations are evidence of his survivalist meanderings. They tell a durational story of his action across the socio-political and physical landscape of space-time. In this sense art can function as memories frozen in documentation and unfold as a form of communication that rides across intersecting trajectories of human life – a form of communication that relies on viewer empathy to engage but also their willingness to take the time to consider the artist’s action.

However, art is inherently a problematic form of communication for it is often shrouded in a multiplicity of possible meanings and interpretations. As such, art also has a propensity for its meaning to shift throughout time as successive waves of individuals own it or engage with it over generations. This flies in the face of art history, which due to its very nature, seeks to rationalise and tidy up inconsistencies so that narratives can be made and understood. In her essay ‘This is so contemporary!’ curator Amelia Groom encapsulates this shifting face of art in contention with art history. She writes:

artistic innovation, replication and mutation never unfold in a single, unbroken direction. History’s movements are turbulent, and art will always refuse to tell a fixed, unified story . . . our segmentation of the past is purely arbitrary and conventional; an imposition of linear order on something that is infinitely more fluid and complex. [43]

Quoting Jorge Luis Borges, she continues that ‘every writer creates his own precursors . . . all worthwhile art modifies our conception of what went before it, and what comes after it . . . historic time is always at once progressive and regressive’.[44] In essence, art is never fixed in ‘history’ but is continually travelling back and forth throughout time as if a long-winded letter between countless agents.

Duane Linklater in his work Very Real Things investigates the implications of art as a form of communication across time, both as a means for connection and also indicative of lost encounters. Here, Linklater pursues a series of correspondence with the Polish artist Joanna Malinowska in which he questions the inclusion of a painting by imprisoned Native American artist and activist Leonard Peltier as part of her contribution to the 2012 Whitney Biennial. Claiming to have ‘smuggled’ Peltier’s painting into the exhibition, Malinowska intended its presence to be a radical gesture of institutional critique by questioning both her inclusion in the biennial and the absence of indigenous art in the Museum.[45]

In his narrated letter, Linklater compares Malinowska’s intervention to Joseph Beuys’ 1974 work I Like America, America Likes Me. He writes to her saying:

The Beuys project like yours takes place in New York City and both projects contain a comfortable separations[b1] between their protagonists (you and Beuys) and their antagonists (Little John and Leonard Peltier). As a side note, the name of the coyote in that piece was Little John and he was from a farm in New Jersey where he had as a handler an older white farmer who controlled his coyote with a large iron rod. But most notably in my opinion both projects attempted to address a sort of wound created by the colonisation in North America and their resulting disparities – very real things . . . Now the gesture of bringing his [Peltier’s] painting into the Whitney generates the juxtaposition of the image of Little John in a room behind a fence at the René Block Gallery in New York City in 1974 and the image of Leonard Peltier behind bars right now, as I write this email to you, at a maximum security penitentiary in Florida. I am thinking of these things right now. I am also thinking that both projects failed in their attempt at recovery.[46]

After outlining his analysis, Linklater proposes a co-authored exhibition with Malinowska as an opportunity to ‘recover something from this series of entanglements and questionable relationships’.[47] His offer is declined by her, concluding with a mutual promise to delete their subsequent communications. In one final retort, Linklater refers to another work by Malinowska in which she appropriates the style of nineteenth-century ledger book drawings by Native Americans. This time Linklater responds by creating a series of three replica ledger drawings in three cities and reflects on the art form as:

an interesting intersection of circumstance art, art production, memory, loss, poetry and something to do with hands. Hands which in spite of binds, which bind them, produce a document which in itself produces a series of feelings, a series of histories, a series of names and contexts, a series of places and things, a series of shapes and colours, a series of buffaloes and horses, a series of lines and shapes, a series of ways of looking and thinking.[48]

In considering Linklater’s work, the durational experience of time is measured through the intervals of personal communication, the effort required to navigate ripples of inherited unresolved trauma from past generations, and the question of art itself as a form of time travel. As time-travelling objects, artworks physically skim across the water of time gathering cultural provenance, as if it were momentum securing their trajectory into the future. Thus the durational is created by a complex web woven together by social interactions, both personal and collective, that accumulate throughout history. It is from the strands of such a web that intersecting moments of exchange and encounter become nodal points from which power relations are both reinforced and contested. Often art eventuates as the physical and conceptual embodiment of such nodal points and sometimes feature as a starring role within a cultural movement at large in a society. In this sense, art can be and has been complicit in forcing ‘very real things’ into tidy abstract logic.

Author Margaret Atwood warns us to ‘watch out for art’ in her post-apocalyptic novel Oryx and Crake in which the Crakers, a race of naive super-humans, have been genetically engineered to repopulate the earth following a global pandemic. [49] In this instance the Crakers’ human caregiver recalls the geneticist’s warning:

As soon as they start doing art, we’re in trouble. Symbolic thinking of any kind would signal downfall . . . Next they’d be inventing idols, and funerals, and grave goods, and the afterlife, and sin, and Linear B, and kings, and then slavery and war.[50]

While she warns us about art, Atwood later concedes that the human attachment to symbolic creation is an irrevocable human mechanism to cope with our corporeal transience. In her sequel novel The Year of the Flood, Atwood suggests that ‘the heart clutches at anything familiar’[51] in order to hold onto the present even though it continues slip through our fingers. Atwood reminds us that the duration of mortality is inherently a lament. ‘Farewell is the song Time sings’ she writes.[52]

This relationship between art and time bears some relation to theorist Roland Barthes’ reflection on photography and death in his book Camera Lucida. Barthes presents us with a Schrödinger’s-cat-like scenario in which our entrancement with the photograph is held in a continual tension between being a representation of both the living and the dead. He writes, ‘whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe . . . there is always a defeat of time in them.’ [53] In Barthes’ line of thought when viewing a photograph we are suspended between the past and present and as such attention is drawn to our own mortality.

__________________

Chuck’s dining table, during breakfast on Thursday, 12 April 2007. I pause after reading of Vonnegut’s passing, struck by the happenstance of reading his novel in the Chicago neighbourhood in which he once studied and on the night that he died. I am reminded that in the opening pages of Slaughterhouse-Five Vonnegut attempts to reconcile his World War II experiences while trying to make sense of his civilian life. He openly shares that after such trauma ‘there is nothing intelligent to say’ because ‘everybody is supposed to be dead . . . everything is supposed to be quiet after a massacre, and it always is, except for the birds. And what do the birds say? All there is to say about a massacre, things like “Poo-tee-weet?”’[54]

This novel, I am left considering with my morning coffee, is the sound of a provocative bird call from someone who, in his own creative way, would shape how subsequent generations might better understand this dark moment in human history. To do so, Vonnegut invented the character Billy Pilgrim who travels in time through his own body and thereby becomes unstuck and re-lives his experiences as a US soldier who survived the horrific firebombing of Dresden. Pilgrim comes to master his transience and ultimately transfigures into a peaceful fourth-dimensional being who reflects philosophically upon his fleeting existence and the folly of humankind to create absurdities such as war.

While art is not the perfect arena to resolve the wrongs of our human failings what it may do is give us insight and understanding into various points of view that may. As with Billy Pilgrim, it is alternative time perspectives that we greatly require if we are to make any decisive shift away from motivations that are in service of the clock but not in the interests of a sustainable future.

[1] Jay Griffiths. Pip Pip: A sideways look at time. London: Harper Press, 2000. p. 157

[2] Terry Smith. Thinking Contemporary Curating. New York: Independent Curators International, 2012. p. 45

[3] Henry Ford. My Life and Work. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1922. p. 73

[4] Frederick Winslow Taylor. The Principles of Scientific Management. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishing, 1911. p. 59

[5] ibid. p. 100

[6] George Orwell. Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Penguin Group, 1949. p. 187–89

[7] Benjamin H.D. Buchloh. Darcy Lange: Paco Campana in Darcy Lange: Study of an Artist at Work. Edited by Mercedes Vicente. New Plymouth/Birmingham: Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Ikon Gallery. p. 59

[8] ibid. p. 56–57

[9] Katerina Gregos. Manifesta 9: Deep of the modern – A Subcyclopaedia, artwork information. Edited by Cuauhtémoc Medina and Christopher Michael Fraga. Milan: SlivanaEditorial, 2012. p. 151

[10] Nicolas Kozakis and Raoul Vaneigem. A moment of eternity in the passage of time, 2012. Digital video, 5 minutes.

[11] Griffiths. Pip Pip. p. 10

[12] ibid. p. 21

[13] George Woodcock. ‘The Tyranny of the Clock’ (1944) in Time: Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art Series. Series editor Iwona Blazwick. London/Cambridge, MA: Whitechapel Gallery/MIT Press, 2013. p. 66

[14] ibid. p. 65–66

[15] Jay Griffiths, Pip Pip. p. 15

[16] ibid. p. 15–16

[17] Matt McGrath. ‘Dissent among scientists over key climate impact report’. BBC News, Yokohama, 25 March 2014. www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-26655779 (accessed 27 March 2014)

[18] Matt McGrath. ‘IPCC climate report: humans ‘‘dominant cause’’ of warming’. BBC News, Stockholm, 27 September 2013. www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-24292615 (accessed 27 March 2014)

[19] Matt McGrath, ‘Dissent among scientists over key climate impact report’.

[20] ‘Some NZ centres may have to be abandoned – climate scientist’. ONE News, TVNZ, 30 March 2014.tvnz.co.nz/national-news/some-nz-centres-may-have-abandoned-climate-scientist-5879454 (accessed 31 March 2014)

[21] Travis Elborough. ‘Reality is a Stage Set’, interview with J.G. Ballard, appendix in The Drowned World, op. cit., pp.1-13

[22] ibid. pp. 4 –5

[23] Ballard. The Drowned World. p. 19

[24] ibid. p. 23

[25] ibid.p. 71

[26] ibid.p. 174

[27] H.G. Wells. The Time Machine. London: Penguin Books, 1895 (2011 edition). pp. 78–79

[28] Ballard. The Drowned World. p. 70

[29]Wells. The Time Machine. p. 82

[30] ibid. p. 85

[31] The Otolith Group. Medium Earth, 2013. Commissioned by RedCat, LA. HD video, 41 minutes

[32] The Otolith Group. Lecture performance at the conference Where Are We Going, Walt Whitman: An ecosophical roadmap for artists and other futurists, Studium Generale Rietveld Academies, Amsterdam, 12–15 March, 2013. www.youtube.com/watch?v=6msLas9sBmg (accessed 15 May 2014)

[33] ibid

[34] The title of this section ‘Billy Pilgrim is unstuck in time’ is from Kurt Vonnegut. Slaughterhouse-Five. London: Panther Books Limited, 1970 (1972 edition). p. 23

[35] News Services. ‘Kurt Vonnegut, known for classic novels, dies’. Chicago Tribune, 12 April 2007. articles.chicagotribune.com/2007-04-12/news/0704120352_1_vonnegut-suffered-brain-injuries-autobiographical-collage-essays-and-short-fiction (accessed 23 April 2014)

[36] Doreen Massey. ‘Some Times of Space’ in Time: Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art Series. pp. 117–18

[37] Henri Bergson. The Multiplicity of Conscious States: The Idea of Duration in Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness, translated by F.L. Pogson, M.A. London: George Allen and Unwin (1910). p. 80

[38] Massey. ‘Some Times of Space’. p. 121

[39] Tehching Hsieh. ‘One Year Performance 1981–1982’ in Out of Now: The lifeworks of Tehching Hsieh by Adrian Heathfield and Tehching Hsieh. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 160

[40] Adrian Heathfield. ‘Walking Out of Life’ in Out of Now: The lifeworks of Tehching Hsieh. p. 39

[41] ibid

[42] ibid. p. 44

[43] Amelia Groom. ‘This is so contemporary!’ (2012) in Time: Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art Series. p. 47

[44] ibid

[45] ‘Joanna Malinowska’, exhibition information, Whitney Biennial 2012, Whitney Musuem of American Art. whitney.org/Exhibitions/2012Biennial/JoannaMalinowska (accessed 13 May 2014)

[46] Duane Linklater. Very Real Things, 2012. HD video, 10 minutes

[47] ibid

[48] ibid

[49] Margaret Atwood. Oryx and Crake. London: Virago Press, 2003 (2004 edition). p. 419

[50] ibid. p. 419–20

[51] Margaret Atwood. The Year of the Flood. Toronto: Anchor Books, 2009 (2010 edition). p. 365

[52] ibid

[53] Roland Barthes. Camera Lucida: Reflections on photography. New York: Hill & Wang, 1980 (1982 edition; translated by Richard Howard). p. 96

[54] Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five. p. 20

[b1]check with rebecca - Daune thinks it is separations originally separation