Curating Share/Cheat/Unite

PUBLISHED IN:

SHARE/CHEAT/UNITE VOL.4

TE TUHI, AUCKLAND

2017-2018

READ THE EBOOK HERE: VOLUME 4

What is at stake is an ethics of curating, a responsibility toward the very methodology that constitutes practice.[1]

— Elena Filipovic

Share/Cheat/Unite explored understandings of social behaviour that contradict common sense and challenge moral assumptions. To service this enquiry, it was important that the curatorial approach also attempted to upend its own social norms by resisting standard exhibition-making conventions and to open up the process so that other practitioners could influence its development. As Elena Filipovic reminds us, the question of methodology is essentially an ethical proposition. For a curator’s motivation, process and framework ultimately shape an exhibition and also have the potential to impact the lives of all the people involved and represented. Given these implications, it is crucial that the curatorial approach is explicitly considered rather than blindly relying on business as usual.[2]

This essay explores my attempt at devising such an ethically responsible curatorial approach in relation to the exhibition’s focus. It is an approach that draws on many aspects that have become clear to me with the benefit of hindsight. In truth, during the process these aspects seemed more like a soup of ideas, provocations and conversations from which an exhibition evolved. And, as I will discuss, the exhibition’s multiple parts acted as a type of mechanism for collective learning rather than a singular and complete cultural product. First, I consider the exhibition’s main focus of artistic practice in relation to social psychology and how that led to creating an agonistic space through artist selection. Second, I discuss the socio-political context that emphasised a relational understanding of the exhibition-making process and a heightened sense of professional responsibility. Third and last, I examine the curatorial framework more specifically by evaluating its foundation within notions of performativity. Throughout, I employ the critical theory of Judith Butler, Doreen Massey and Chantal Mouffe among others to provide a basis to the curatorial process alongside other integral exhibition-making roles.

AGONISTIC ARTIST SELECTION

The three thematic threads of Share/Cheat/Unite: altruism, cheating and group formation were a helpful lens through which to explore the crossover between art and social psychology. Since the 1960s artists who directly address social relations have engaged with these aspects of human behaviour in a myriad of ways, including seminal performance works such as Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1965) and Marina Abramović’s Rhythm 0 (1974) that simulated how a vulnerable subject can be easily dehumanised within a particular social context. Or works such as Santiago Sierra’s paid works of the 1990s and Tania Brugera’s Tatlin’s Whispers #5(2008) which confronted audiences with the institutional systems that control human agency and set the conditions for injustices that we are all complicit in maintaining. Such artworks parallel research conducted within the discipline of social psychology, ranging from Stanley Milgram’s 1961 obedience to authority study, which sought to test human submission, through to John Drury’s theory of collective resilience in the early 2000s, which redefined assumptions of crowd dynamics in disaster situations.[3]

In venturing down this path, drawing connections between art and social psychology, it is important to highlight that the two disciplines and their practitioners couldn’t be more different. Let’s face it—artists are not always the most helpful people to have involved in social issues, precisely because they usually lack the knowledge and expertise that scientists and other specialists possess. With a lack of expertise, artists can get it considerably wrong. The pitfalls are now well known and hotly debated: a) the young, educated and well-dressed art-world clique flies into an ‘underprivileged’ context with the assumption they can tackle topics the locals can’t; b) the misplaced argument that social engagement must be positive at all costs; c) the misunderstanding of specific cultural contexts or a lack of knowledge to address a given situation while acting with confidence and privilege regardless; and d) the accusation of faking or coercing participation for a picture-perfect outcome. In addition, it is all too easy to become optimistic when creating art that attempts to address immeasurably complicated issues of social formation. But it doesn’t matter how egalitarian or engaging an artwork might appear, the potential for unintended consequences is high because ultimately artists have finite power, skills and resources to adequately tackle complex social issues. As Claire Bishop explains:

participatory art is not a privileged political medium . . . but is as uncertain and precarious as democracy itself; neither are legitimated in advance but need continually to be performed and tested in every specific context.[4]

Also, the most pressing social issues we face are usually the direct result of capitalist and neoliberal forces that can co-opt art at every turn. Such forces require greater power than the effort of any one individual or subset of society can summon alone. As the political theorist Chantal Mouffe writes, ‘It is an illusion to believe that artistic activism could, on its own, bring about the end of neo-liberal hegemony.’[5] Artists may not be the solitary creative geniuses or possessors of social conscience that curators, myself included, have built them up to be. Yet despite these problems artists are irrevocably embedded in the social fray. And at best, artists cancontribute profound moments of political clarity, fleeting glimpses of lateral thinking, empowering situations of social cohesion or fervent sparks of provocation—contributions that Mouffe would class as agonistic strategies: counter-hegemonic moves creating new subjectivities, and the disarticulation of common sense which enforces social norms.[6]

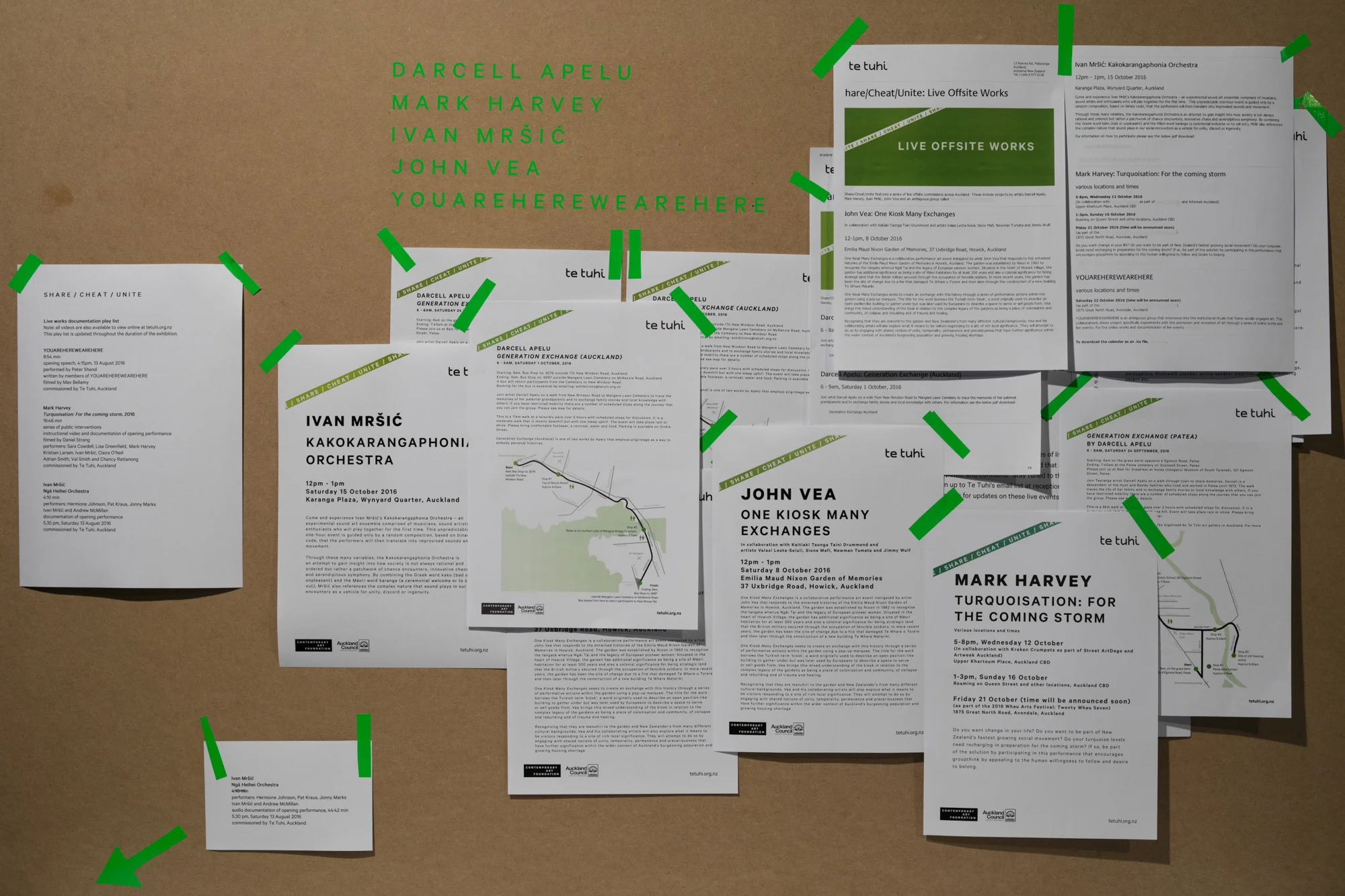

Graphic design by Kalee Jackson. Exhibition design by Andrew Kennedy. Photo by Sam Hartnett.

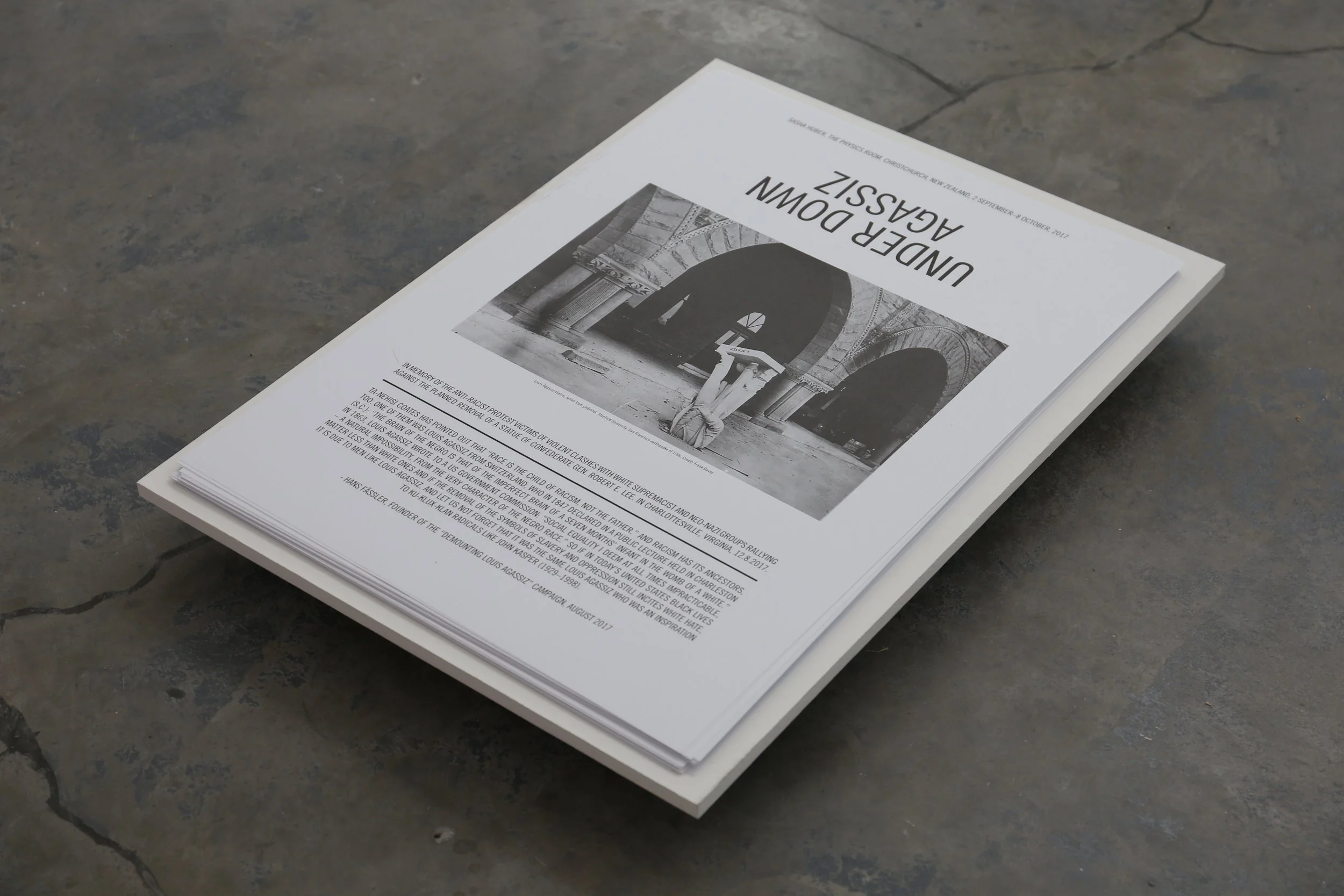

By acknowledging such positive and negative complications, when curating Share/Cheat/Unite, we aimed to feature and support a multiplicity of artistic practices that sat uncomfortably with each other. Consider the moral crusade exemplified in Sasha Huber’s body of work Demounting Louis Agassiz (2008—)[7], to the ethically murky work Testimonio (2012) by Aníbal López.[8] Few would deny that Huber’s attempt to draw attention to the historical vestiges of racism is a noble act. Whereas López’s work, which brought a sicario (contract killer) from Guatemala to Germany for dOCUMENTA 13, never failed to divide opinion between those who considered the artist’s action as abhorrent, unethical or dangerous and those who extolled the virtue of this confrontation. Or consider the reverent performances by John Vea and his collaborators in One Kiosk Many Exchanges(2016)[9] to the deadpan satire found in Mark Harvey’s performance cult in Turquoisation: For the coming storm(2016).[10] Vea’s form of collaboration is unquestionably heartfelt with a sincere attempt at learning about and spending time with others to strengthen a sense of community. Whereas Harvey’s work is more cynical by demonstrating how group cohesion can be created under an inane pretence, perhaps for nefarious neoliberal or capitalist motivations.

Each of these selected artists identify with different ethical positions and aesthetic persuasions within the artworld, positions that are so often diametrically opposed. But via the exhibition and linked together through live discussions and publications, these contestable elements were brought into a context of healthy debate rather than the comfort of smooth consensus. It was hoped that these tensions between artworks might also encourage debate among audiences as they walked through the gallery or experienced the live and published components. Again, this is what Mouffe would consider an agonistic space in which ‘conflicting points of view are confronted without any possibility of a final reconciliation’—a goal which she argues is essential for revitalising the potential of democracy in our neoliberal age of centrist politics and rampant capitalism.[11]

However, creating an agonistic space through artist selection as a curatorial strategy can have its pitfalls. Especially if the debate, internally and externally of the exhibition, becomes the main focal point rather than the artworks themselves. In this scenario, where emphasis might shift from the artist to that of the curator, the artworks could merely become ingredients within a master curatorial narrative. Or in an even worse scenario, the artists themselves could become subjects within a social experiment devised by the curator. These outcomes would distract greatly from the concerns of the individual artworks and the people they represent, not to mention the numerous ethical implications for the artist–curator relationship. It is difficult to ascertain whether Share/Cheat/Unite was complicit in creating these types of outcomes. But it is certainly a question worth pursuing, at least in a more general capacity in regard to curatorial approaches that seek to critically consider artist selection.

EXHIBITION POWER-GEOMETRIES

The ethics of artist selection and agonistic space brings us to the importance of engaging in a wider socio-political context beyond an art-specific discussion and how an exhibition can engage in this by considering the relational construction of space. There is no escaping that exhibitions, in their most conventional and unconventional sense, are spatially constituted. If we accept this proposition, then it is imperative that we expect that an exhibition’s making must bear some responsibility to the many relations it creates in the space and to the space in which it resides. As the geographer Doreen Massey argues, space is ‘the product of interrelations . . . from the immensity of the global to the intimately tiny’.[12] If space is the product of relations then, Massey continues, it ‘raises questions of the politics of those geographies and of our relationship to and responsibility for them.’[13] She terms this ‘power-geometries’—the spatial product that is made through power relations and through which such relations flow.

With this socio-political and relational understanding of space in mind, coupled with the topic of social psychology, it was important that Share/Cheat/Unite’s artists, curators, writers, designers and gallery staff addressed its responsibility to the power-geometries of its making. This provocation naturally emphasised the local, national and international socio-political context that paralleled the exhibition’s development and realisation—spanning a time period between late 2014 to mid-2018. For instance, the exhibition research began in the shadow of Aotearoa New Zealand's 2014 election in which the National Party gained a third consecutive term in power, despite allegations of dirty politics alongside climbing statistics of homelessness, a widening divide between rich and poor and an increase in environmental degradation.[14] For some people on the left of the political spectrum, this election outcome came as a great shock. ‘But I don’t know anyone who voted for National’ was a common cry, despite the fact that the vast majority of the voting population clearly supported National.

This shock revealed a social blind spot, influenced to a significant degree by the biases imbedded with the algorithms that drive online platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Google. Such platforms encourage personal preference and similarity with others rather than an interest in or tolerance for difference. The so-called digital silos and echo chambers that these algorithms are said to create perpetuate a hyper-personalised perception of the world. As I discussed in Volume 2 of Share/Cheat/Unite, under these circumstances, when a hyper-personalised reality collides with the actual democratic reality of a nation, it is no wonder that shock and even outrage ensue. Following this logic further, it is conceivable that if populations become more virtually distanced their civility could erode when a particular group feels threatened. The UK’s Brexit referendum in 2015 and the succession of Donald Trump in the US election in 2016 similarly produced a climate of radically polarised political views and shock among those of a liberal persuasion.

The 2014–18 period was also a time of intensified social tension. Social media aided movements such as Black Lives Matter[15] in the US and the more global #metoo[16] phenomenon sparked a new wave of speaking truth to power. Social justice strategies of this time also involved community self-policing through callout culture, which in some cases circumvented the process of state institutions by implementing varying degrees of public shaming, protest and ostracisation.[17] These political events and social movements provided textbook examples of social psychological phenomena that were integral to the sub-themes of Share/Cheat/Unite. Producing an exhibition while these issues permeated our lives was a humble reminder, for the artists, curators, writers and gallery staff involved, that the topics in question were pertinent to current events and had the potential of making an immediate contribution to a larger conversation. This sense of duty within a flow of power relations brings us back to Massey’s understanding of the politics of space. ‘To the degree that it is a social and political product,’ Massey writes, ‘there is therefore always the crucial ethical and political question of how it is constructed, and our duty in relation to that.’[18] Therefore, by occupying space, in a simultaneity of social and political relations, exhibitions are unavoidably charged with the ethical responsibly of their making. Similarly, as the socio-political context shifted over the four-year duration of the Share/Cheat/Unite project so too did the making of the exhibition increase in a responsibility to reflect that.

One other aspect of exhibition power-geometries is that the socio-political responsibility must be made manifest throughout all of its constitutive parts not just ideologically stated in the curator’s essay or speech. The exhibition’s material, communicative and social forms mustsupport the agency for those socio-political issues it claims to address. This idea is reinforced by the political theorist Judith Butler who through a performative analysis of public assembly writes that

politics is already in the home, or on the street, or in the neighbourhood, or indeed in those virtual spaces that are unbound by the architecture of the house and the square . . . Human action depends upon all sorts of supports . . . the capacity to move depends upon instruments and surfaces that make movement possible, and that bodily movement is supported and facilitated by non-human objects and their particular capacity for agency . . . those material environments are part of the action, and they themselves act when they become the support for action.[19]

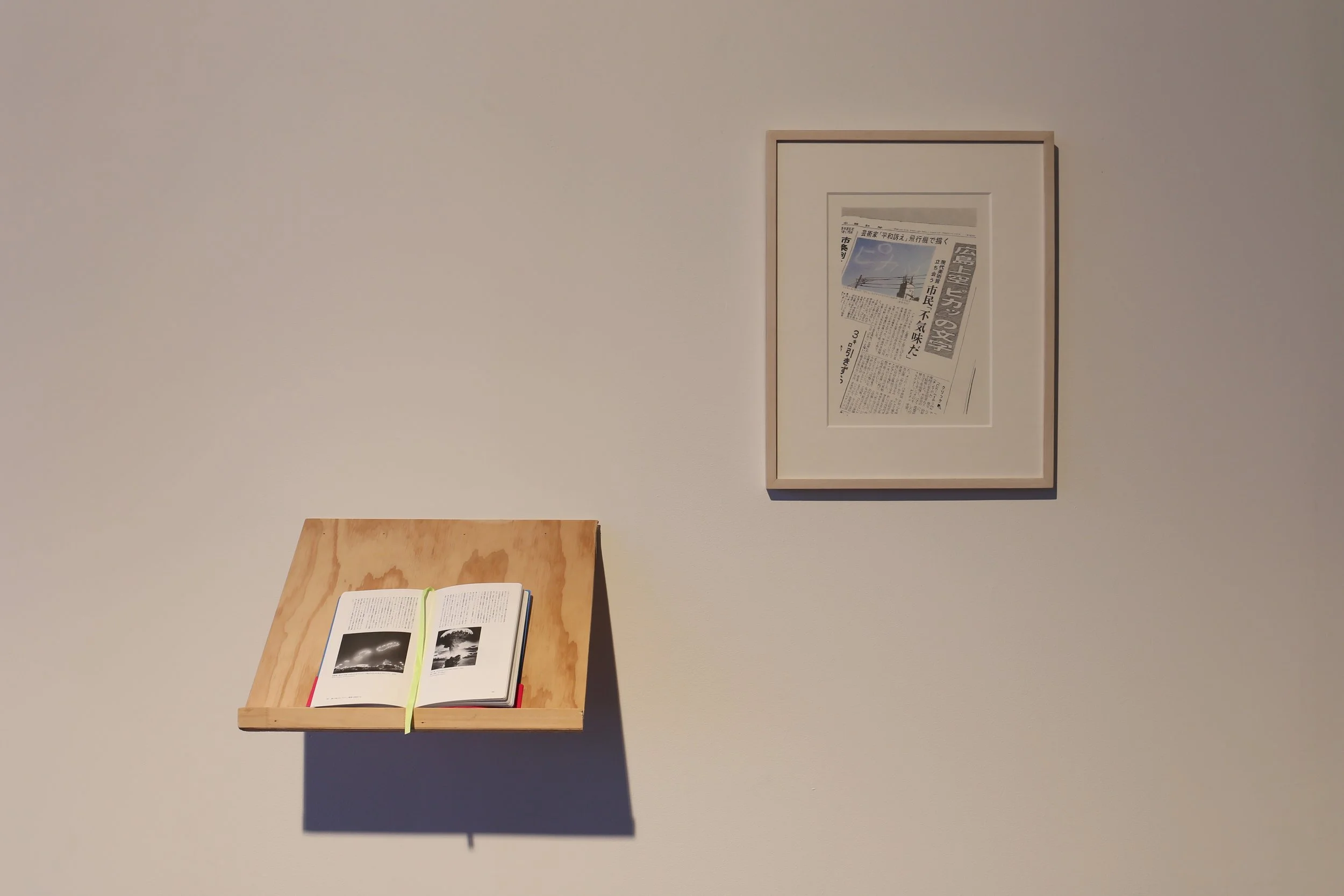

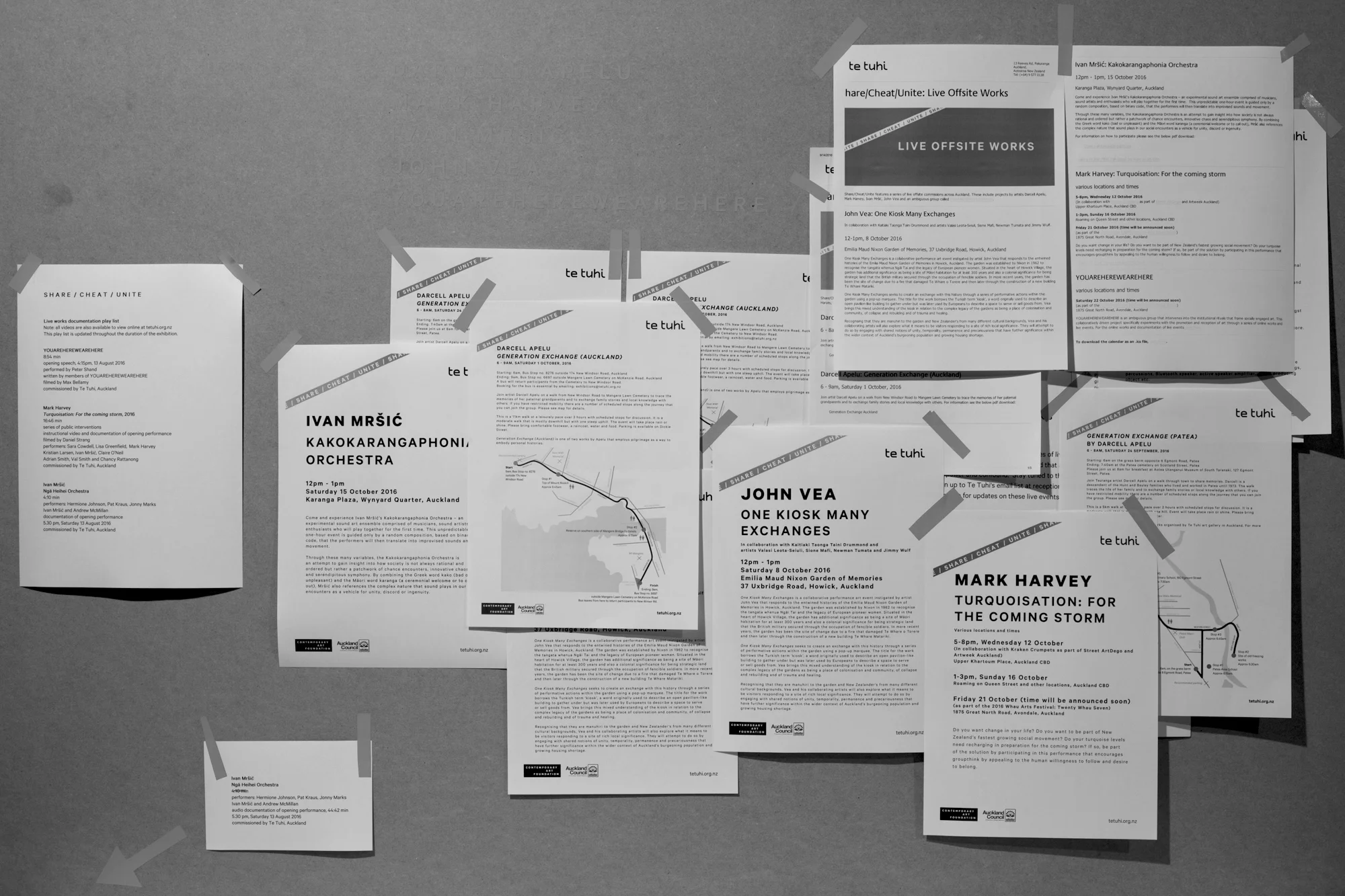

Share/Cheat/Unite embraced a similar understanding to Butler’s insistence that agency is contingent on the design of an environment. This was carried throughout all of the exhibition’s material, communicative and social parts to make them visible, accessible and suitable to support action. This was implemented through numerous live events in public spaces, discussion groups, free digital publications, video documentation posted online and so on. Graphic design by Kalee Jackson and exhibition design by Andrew Kennedy also contributed, especially in the Te Tuhi iteration. Exhibition signage lured people into the galleries through a vibrant green linear masthead that darted between the gallery spaces. Reading tables, noticeboards and partitions created out of humble materials such as MDF board and tarpaulins created a functional and unpretentious space and gave easy access to contextual material.

The social generosity of those involved was also important. Front of house staff welcomed and provided information to audiences. Collective social labour, such as hosting shared meals and facilitating group conversations, performed by the Te Tuhi and Physics Room teams and invited external practitioners, added critical thinking to the discussions in the concept development, engaged with the artists and supported them. Such material, communicative and social contributions are easily overlooked but are essential for an exhibition to fulfil its responsibility to a given context. Without this collective effort, exhibitions would fail to become active. They would be inert artefacts with little impact within the relational flow of ever-changing power-geometries.

PERFORMATIVE CURATING

The first two parts of this essay considered the fraught artistic and socio-political contexts and how the motivation and responsibility of the exhibition-making contributed to a greater conversation. I will now explore the curatorial framework, the theoretical influence of performativity and how the ordering of the exhibition led to a multiplicity of components with ethical aspirations. The focus of performative curating as a methodology differs greatly from more conventional institutional practices due to its grounding in a post-structuralist paradigm[20]—in particular the linguistic analysis of John L Austin who in the 1950s argued that the act of speech is a performative utterance that constitutes the doing of something in the world through words and signs.[21] This was later expanded by theorists such as Judith Butler who used Austin’s analysis and applied it to the social construction of gender norms, revealing it as ‘an identity instituted through a stylized repetition of acts’.[22] This shift from speech acts to social acts enabled the notion of performativity to be applied to broader forms of cultural production such as theatre, visual art and ultimately curating.[23] Within curatorial practice the questioning of power relations built within linguistic and social actions are easily applicable to exhibitions. This is articulated by curator Katharina Schlieben who explains that performativity within curating requires the ‘procedural and productive realisation’[24] of an exhibition to be transparently revealed and explicitly considered.[25] This ultimately leads to the importance of consciously creating a curatorial framework that resists the conventional practices that might easily undermine these principles. With this model of performative curating in mind, Share/Cheat/Unite was divided in three parts: a gallery-based group show and a research initiative held at Te Tuhi; a series of live offsite commissions at various locations across Auckland and in Patea; and a subsequent exhibition and related activities at The Physics Room in Christchurch.

The group show featured an international selection of existing artworks that touched on aspects of altruism, cheating and group formation bound within moments of social exchange, and included works by Hu Xiangqian, Aníbal López, Sasha Huber, Jonathas de Andrade, Yu-Cheng Chou, Vaughn Sadie and Ntsoana Contemporary Dance Theatre. These artists unpacked various aspects of social behaviour by addressing a range of topics through photography, graphic design, alternative histories, documented performance and collaborative and video-based practices. Admittedly, by virtue of taking place in a ‘white cube’ institutional space, this gallery-based component unavoidably relied on conventional curatorial practice, but it also functioned as a conceptual and physical anchor for the exhibition as a whole—a site through which the more temporal projects were documented and promoted, a space where local issues could be considered as part of a global conversation and a platform that initiated discussion.

This space for discussion became an important factor for the research initiative that was run by artist and academic Melissa Laing. This month-long programme of discussions explored the importance of conversation in life and artistic practices. The research initiative took place at Te Tuhi alongside the exhibition in 2016 and then continued as an independent group in 2017. This series of discussions became titled ‘Navigating Conversational Frequencies’. The culmination of lived experiences and theories raised during these discussions and in similar projects is elaborated on further in this ebook in Laing’s essay ‘Some Parallel Discussions’. The live offsite commissions aimed to entice, empower and confound. These included projects by artists Darcell Apelu, Mark Harvey, Ivan Mršić, John Vea and an ambiguous movement called YOUAREHEREWEAREHERE. Various artworks from the group show and the live offsite commissions are discussed at length throughout the first three volumes of the Share/Cheat/Unite e-book series.

The performative approach was also emphasised through a process that encouraged emerging propositions to be collectively eked out rather than respond to a didactic curatorial theme. For instance, in the commissioning process for the live offsite works, the artists and other participants were invited to debate, collaborate and even rewrite the curatorial direction.[26] These discussions began with a shared dinner in December 2015, in which the participants were given a range of ingredients and recipes and were asked to self-organise to make the meal. This simple exercise demonstrated how, even in a group self-consciously gathered to discuss aspects of social psychology, people automatically fall into particular roles and engrained social dynamics eventually take hold. The subsequent group meetings enabled the collaborative movement YOUAREHEREWEAREHERE to evolve, through which the artists Darcell Apelu, Mark Harvey, Ivan Mršić and John Vea were able to freely experiment outside of their individual practices. Under the YOUAREHEREWEAREHERE moniker, the artists infiltrated the exhibition opening with a nonsensical speech, took over Te Tuhi’s social media accounts and conducted a happening during the 2016 Whau Arts Festival.[27] The mischievous nature of these interventions are discussed in Volume 2.

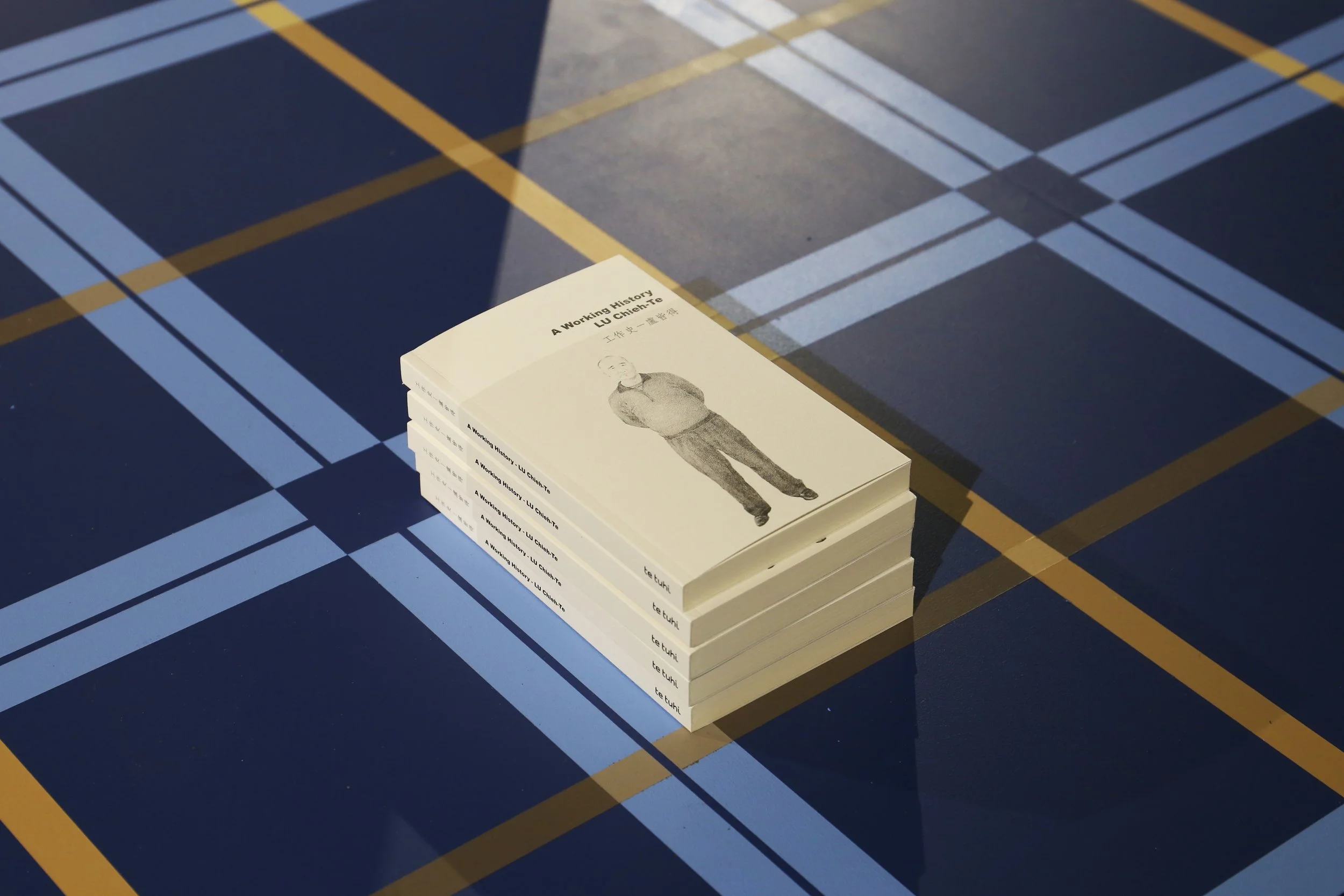

The performative ethos of Share/Cheat/Unitebranched out to spark a conversation with other curators and art organisations. Through this invitation it was hoped that the exhibition might become an unpredictable forum that unfolded over time and which encouraged discussion and participation. As a result, a version of Share/Cheat/Unite was curated by Jamie Hanton at The Physics Room in Christchurch, including work by Gemma Banks, Yu-Cheng Chou, Sasha Huber, Aníbal López (A-1 53167), Chim↑Pom, Pilvi Takala and Johnson Witehira. Similar to the Te Tuhi version, The Physics Room curatorial process also included shared meals, conversations and offsite components that helped shape the show. Essays by Hanton reflecting on this exhibition and its relevance to the post-quake context of Christchurch are included in this e-book.

Considering this multi-format and process-based curatorial framework highlights a glaring challenge of performative curating—that it is difficult to evaluate an exhibition that shapes its procedural structure as a performative element. Especially when that procedural structure has numerous parts stretching over multiple locations and occurring over a four-year period. Therefore, it is hard to determine whether Share/Cheat/Unite managed to ‘scrutinise artistic practice’ or to seek out the ‘emerging propositions’ of curating as was claimed earlier. In hindsight, these objectives are far too abstract and broad to ever be achieved and the performative approach is too dispersed, porous and plural to easily gain a tangible understanding of it. At best these objectives and processes helped frame a certain context from which expectations were made, agency was shared and discussions were set in motion. These factors enabled Share/Cheat/Unite to be less of an ‘art exhibition’ as such and more of a type of social mechanism through which learning, experimentation and conversation could be attained from all points of contact—from the curators, gallery staff, artists and the public through to the platforms of live offsite events, discussion groups, gallery-based exhibitions, publications and everything in between.

Just because a curator might be guided by a particular methodology doesn’t guarantee that they won’t perpetuate the very hegemony they are claiming to resist. Additional perspectives and bodies of knowledge that demand a critical consideration of a curator’s responsibility then are incredibly important. In recognising this I made an intuitive decision to intersect a performative curatorial approach with other theories discussed earlier such as Mouffe’s assertion that art should be active within and activate a multiplicity of agonistic public spaces to encourage democratic contestation.[28] I also embraced the provocation put forward by Massey, who argues for an understanding of space as a flow of multiple relations that construct and are constituted by power-geometries.[29] Judith Butler’s assertion that the configuration of space enables agency and is in turn made by the action it empowers. By drawing in these additional theoretical influences, it could be argued that Share/Cheat/Unite was able to apply a performative curatorial approach in a way that had intersectional points from which to question the validity and purpose of its framework.

[1]Elena Filipovic, ‘What Is an Exhibition?’, in Jens Hoffmann ed, Ten Fundamental Questions of Curating(Milan: Mousse Publishing, 2013), 67.

[2]Maria Lind, ‘Active Cultures: Maria Lind on the Curatorial’, Artforum, October 2009, https://artforum.com/inprint/issue=200908&id=23737.

[3]Roger Ball and John Drury, ‘Representing the Riots: The (Mis)use of Statistics to Sustain Ideological Explanation’, Radical Statistics106 (2012): 4–21.

[4]Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship(London and New York: Verso, 2012), 284.

[5]Chantal Mouffe, Agonistics: Thinking The World Politically, 1stedition (London and New York: Verso, 2013), 99.

[6]Ibid, 99

[7]See Share/Cheat/Unite, Volume 1, 29–31.

[8]See Share/Cheat/Unite, Volume 2, 41–42.

[9]See Share/Cheat/Unite, Volume 1, 31–32, 45–55.

[10]See Share/Cheat/Unite, Volume 3, 22, 43–59.

[11]Mouffe, Agonistics, 92.

[12]Doreen B Massey, For Space, 1st edition(Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2005), 9.

[13]Massey, 10.

[14]Nicky Hager, Dirty Politics: How Attack Politics Is Poisoning New Zealand’s Political Environment (Nelson, New Zealand: Potton and Burton, 2014).

[15]The Black Lives Matter movement was founded in 2013 but didn’t receive global notoriety until 2014 due to the street protests in reaction to the police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner in New York City.

[16]The use of the phrase ‘me too’ to reveal the widespread issue of sexual harassment has been accredited to civil rights activist Tarana Burke as early as 2006. However, it wasn’t until 2017 that the phrase gained international attention due to its promotion by Hollywood actresses Alyssa Jayne Milano, Gwyneth Paltrow, Ashley Judd, Jennifer Lawrence and Uma Thurman among many others.

[17]Sarah Schulman, Conflict Is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, and the Duty of Repair(Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2016) 71; Ira Glass, ‘637: Words You Can’t Say’, This American Life, https://www.thisamericanlife.org/637/transcript (accessed 13 June 2018).

[18]Doreen Massey, ‘Tokyo Lecture: Geography and Politics’, Geographical Review of Japan Series B 87, no. 2 (2015): 76–79, https://doi.org/10.4157/geogrevjapanb.87.76 (accessed 10 August 2018).

[19]Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly(Cambridge, Mass and London: Harvard University Press, 2015), 71.

[20]Katharina Schlieben, ‘Curating Per-Form’, Kunstverein München, 2007, http://www.kunstvereinmuenchen.de/03_ueberlegungen_considerations/en_performative_curating.pdf (accessed 23 May 2008); Claire Doherty, ‘Performative Curating’, in eds Brigitte Franzen, Kasper König, and Carina Plath, Sculpture Projects Muenster 07K (Köln: W. König, 2007), 413–14.

[21]J.L Austin, How to Do Things with Words: Second Edition, eds JO Urmson and Marina Sbisà, 2nd edition(Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1975).

[22]Judith Butler, ‘Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory’, Theatre Journal40, no. 4 (1988): 519, https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893 (10August 2018).

[23]Joanna Warsza and Florian Malzacher, eds, Empty Stages, Crowded Flats. Performativity As Curatorial Strategy: Performing Urgencies 4, 1st edition(Berlin: Alexander Verlag, 2017).

[24]Schlieben, ‘Curating Per-Form’, 2; Butler, ‘Performative Acts and Gender Constitution’, ibid, 3.

[25]Nina Möntmann, ed, ‘Curating with Institutional Visions: A Roundtable Talk’, in Art and Its Institutions: Current Conflicts, Critique and Collaborations, (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2006), 28–59; Doherty, ‘Performative Curating’; Schlieben, ‘Curating Per-Form’.

[26]Additional participants included curators Balamohan Shingade, Jamie Hanton and Charlotte Huddleston, and artists Fiona Jack, D.A.N.C.E. Art Club and Jeremy Leatinu‘u, as well as Te Tuhi staff.

[27]As part of the 2016 Whau Arts Festival: Twenty Whau Seven, 1:15–5pm, 22 October 2016, outside Salvation Kitchen, 1843 Great North Road, Avondale, Auckland.

[28]Mouffe, Agonistics.

[29]Massey, ‘Tokyo Lecture 66’ ibid.