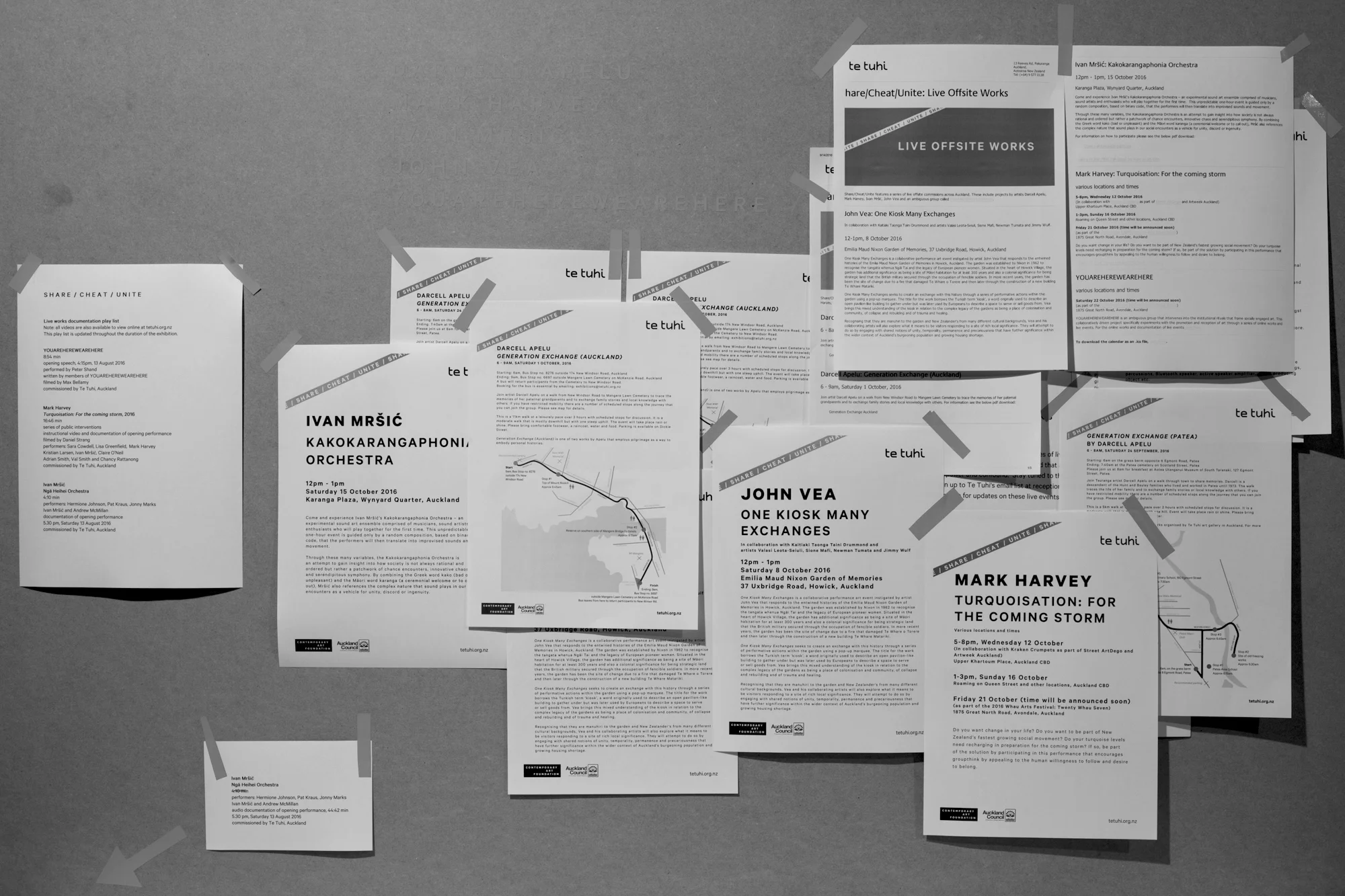

Share/Cheat/Unite

Sasha Huber, Karakia – the resetting ceremony, 2015 (video still), featuring Jeff Mahuika (Kāti Māhaki, Poutini Kāi Tahu). Courtesy of the artist.

Share

ʻWant to share an update, Bruce?’ Facebook asks me within the field of an empty message window. By tapping the screen I publish a post. My message is not life-changing in any way, but it has triggered a minute spike of dopamine in my brain, creating a momentary feeling of satisfaction. As frivolous as it might sound, this feel-good moment of posting a banal Facebook update actually cuts to the heart of what it means to ʻshare’—revealing that sharing is never really purely an altruistic act. On Facebook, we ʻlike’ other people’s posts in the expectation we’ll be liked in return. We become a ʻfriend’ in order to gain friends. We ʻshare’ other people’s posts in the anticipation of having our own posts shared. This giving in order to receive makes us feel individually valued and connected to something larger than ourselves.

ʻWe long to have the world flow through us like air or food’, claims writer Lewis Hyde in his seminal book The Gift:Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World.[1] Written decades before the internet, Hyde’s description of the human animal as a conduit for social relations still holds relevance today. Hyde’s analysis of gift giving is based on a study of fairy tales and indigenous lore that illustrate pre-capitalist models of gift exchange. These are founded on the basic principle that ʻthe gift must always move’[2]—if the circulation of the gift stops, there are consequences. For the economy of sharing to flow without the fabled penalties, Hyde states that the gifts within the system should be a catalyst for creating new life. He argues that art has the potential to be this creative force in our lives—to be an ʻagent of transformation’ that will enable intergenerational learning.[3] Within a conversation about reciprocal intergenerational giving, Yu-Cheng Chou’s artworkA Working History of LU Chieh-Te(2012–) offers a compelling example to consider. To initiate this work Chou placed a job advertisement in a local newspaper that simply read:

HELP WANTED

Temporary job, 50-60 aged male or female

Work location: Zhonghua Road

Taipei City, Call 0956259XXX

From these few words, Chou made a connection with a man named Chieh-Te Lu and a project unfolded that also grew into a long-lasting friendship. The main component of the project is a book which tells Lu’s life story––in particular the story of his working life, which is a tale of hard labour but also navigating certain societal expectations and personal demons. His story begins with his father disowning his mother, then being orphaned at age four due his mother’s violent death at the hand of his stepfather. This formative trauma would shadow his working life, which consisted of a wide array of professions including rice farming, military service, stunt work for films, ticket scalping, and for the most part working in hospitality. In his middle age, late-night gambling and heavy drinking led to a near-fatal car accident and signalled a turning point in his life to focus on health and family. Chou explained to me that a requirement for exhibiting the book is that Lu is to be employed by the gallery as an invigilator––so he can share his story one to one with visitors and also so the project will extend his employment history. The first public staging apparently led to Lu becoming a well-known face amongst the Taipei art scene. By the time the project was exhibited at Te Tuhi and The Physics Room, Lu turned down the offer to extend his résumé, opting instead to retire from the workforce.

Yu-Cheng Chou, A Working History Lu Chieh-Te, 2012. Installation, booklet (Chinese & English), 13 x 21 cm, 210 pages, pattern painted on wooden deck, 500 x 500 cm. Commissioned by Taipei Contemporary Centre in Taipei for the exhibition Trading Futures, 2012. Commissioned by Te Tuhi in Auckland for the exhibition Share/Cheat/Unite, 2016. Photo by Sam Hartnett

Through this project, Chou opened up an opportunity for a previously unheard voice to share their life but also to enter into a contract that offered remuneration, ongoing future employment, social recognition and friendship. Chou also benefitted, through the cultural capital gained by establishing a socially beneficial project that then resulted in his work being exhibited around the world. Considered from a sociological perspective, the project could be understood as a representation of a particular demographic in Taiwanese society who struggle to find employment, or else a reflection of the shift in Taiwan’s history from an agricultural to industrial economy—a history that is also tied to successive waves of migration, colonisation and capitalism.

In this sense, Chou’s artistic contribution engages in a very real system of reciprocal giving that was transformative within Lu’s life, transformative in Chou’s career and also has the potential to become transformative for others. Exhibition visitors have the opportunity to take home a free copy of the book, to read it over time or give it away to someone else. The work literally and symbolically circulates in multiple contexts at once, ranging from the personal to the public. It is the inexhaustible meta-contextual aspect of this project that resonates with Hyde’s assertion that art has the potential to be much more than a luxury possession or commodity. He writes:

The true commerce of art is a gift exchange, and where that commerce can proceed on its own terms we shall be heirs to the fruits . . . to a creative spirit whose fertility is not exhausted in use . . . and to a sense of an inhabitable world—an awareness, that is, of our solidarity with whatever we take to be the source of our gifts, be it the community or the race, nature, or the gods.[4]

Hyde’s assertions are easy to write off as idealistic. In our age of neo-liberalism and global capitalism, all forms of creative labour can be commoditised to perpetuate cycles of selfish taking rather than equally beneficial exchange. Indeed, artists are also imperfect and may unwittingly create systems of exploitation under the guise of altruistic gift exchange. Hyde’s proposition could also be considered problematic when considered in relation to the complexities of our evolutionary drive. After all, isn’t evolution essentially a type of war, pitting species against species and animal against animal in an incessant contest of birth and death? It seems the answer to this question is far from definitive. Humans are not as bereft of altruism as we might assume. As evolutionary biologists have long known, altruism does not just exist in humans but is rife throughout nature.[5] Early on, Charles Darwin identified altruism as a conundrum for his theory of evolution. In his 1873 book The Descent of Man,he suggests that humans may have won evolutionary advantage not from being the biggest and strongest, but by being small and weak yet smart and social.[6] Despite Darwin’s hypothesising, altruism remained a great paradox for over a century, until 1967, when the inventor and mathematician George Price formulated the covariance equation (commonly known as the Price equation). Science writer Owen Harman explains that the Price equation contains a profound universality that would hold true for ‘a child choosing radio channels to . . . the culling of chemical crystals in far-off galaxies. But it could also be applied to biological traits like baldness and strength . . . and . . . to the evolution of social behaviours like altruism’.[7]

The Price equation essentially reveals that we are mathematically more likely to favour those who share genetic similarity. Subsequent studies on bias, explored by science writer Michael Bond, reinforce the premise, suggesting that people will instinctively ʻcategorize people on the flimsiest of pretexts’ and show a preference towards those who share covariance in anything from the colour of their eyes to the colour of their shirt.[8] When we do good to others we are fulfilling an instinct to maintain the covariance of a group and in turn make certain that our genes or other similarities will survive. This is not done consciously—it occurs at an instinctual level. The equation is deeply encoded within us.

While solving a great riddle, Price’s work also dispelled the notion of altruism being a true act of selfless giving and challenged the special qualities we commonly consider to be human.[9] The reality of the Price equation is particularly chilling in our current situation, in which it seems that technological developments have charged ahead far faster than our biological evolution. Today, many of us receive information filtered and amplified via social media networks governed by algorithms that create a hyper-personalised perception of the world. If we apply the logic of the Price equation to the effects of this new technology, it makes perfect sense that people would become increasingly entrenched and divided. It is simply more attractive for humans to show bias towards a correlating reality than to accommodate an alternative view. Under these circumstances, when a hyper-personalised reality collides with the actual democratic reality of a nation it is no wonder that shock and even outrage ensue.[10] Following this logic further, it is conceivable that if populations become more virtually distanced their civility could erode when a particular group feels threatened.[11] How do we avoid this? How do we manipulate the Price equation so that we can compensate for our biology and fear-based rhetoric before we tear apart our social fabric? How do we create an altruism that is biased towards a love of difference?

According to social psychologist Ashtosh Varshney, the key to social harmony is to resist creating self-interested similarities with one another.[12] Varshney argues that we need to promote integration and civic engagement at a deep level, embedded within aspects of communal life, to ʻfocus on dignity, self-respect, and recognition’ of difference.[13] Sasha Huber’s ongoing body of work Demounting Louis Agassiz (2008–) is particularly poignant as an example of this thesis. Huber has been committed to challenging the legacy of the prominent Swiss glaciologist Louis Agassiz, whose name is attached to many places, geological features and public buildings the world over. Agassiz was a well-known nineteenth-century glaciologist and geologist, a key figure in the discovery of evidence for ice ages [14]—a radical theory in his time.[15] However, his hypothesises on human origins were highly questionable. He pioneered the racist ideologies of polygenism—a spurious theory that purports to provide a scientific basis for a God-ordained racial order placing Caucasians as superior over people of darker skin colours. Agassiz’s vile pseudo-science won popularity amongst slave owners particularly in the South of the United States after he moved there in 1846. His fame as a geologist gave scientific credence to policies of segregation and dehumanisation.[16]

Sasha Huber, Louis Who? What you should know about Louis Agassiz. Intervention, Praça Agassiz, Rio de Janeiro, 2010. Commissioned photography by: Calé, © Sasha Huber. Intervention, Praça Agassiz, Rio de Janeiro, 2010. Video, 3:50 min.

In the Demounting Louis Agassiz series of videos, Huber is documented arriving at locations around the world named after Agassiz, then attempting to rename them or to increase awareness about the racism imbedded in their name. By helicopter she flies to the summit of Agassizhorn of the Bernese Alps in Switzerland and hammers a plaque into the snow—an attempt to singlehandedly rename the mountain ‘Rentyhorn’ after a Congolese slave named Renty whom Agassiz photographed in 1850.[17] On horseback she rides down a street towards Praça Agassis in Juiz de Fora, Brazil, nails a banner to a building and, loudhailer in hand, addresses the public.[18] Via helicopter yet again, Huber soars up the face of a seemingly impassable ice wall in Aotearoa New Zealand, eventually arriving at Agassiz Glacier, a tributary of Kā Roimata o Hine Hukatere[19] (Franz Josef Glacier).[20] She is accompanied by Jeff Mahuika (Kāti Māhaki, Poutini Kāi Tahu), who recites a karakia to clean the glacier of Agassiz’s name.[21]

In Agassiz: The Mixed Traces Series(2010–), a number of photographs show Huber naked in various Agassiz-named landscapes in Brazil, Switzerland, Scotland, New Zealand, the United States and Canada. Huber poses in anterior, lateral and posterior positions, using the same objectifying ethnographic techniques employed by Agassiz to document African people. Each anatomical elevation is performed by Huber on site and superimposed in one image, as if her entire self is scrutinised in a single defining take. The individual images carry numerous layers of significance due to the social and geographical histories of each location, but as a series they reinforce one clear message: Agassiz’s geological fame is inseparable from his racist influence. He considered people of colour not as humans but as natural phenomena to be examined and conquered by his observational intellect. As a person of Haitian and Swiss descent, Huber’s bodily presence in the images is also a defiant gesture—her mixed ancestry would have been deplorable to Agassiz. Considering the photographed action as a form of protest, Huber also connects with the proud Haitian legacy of dismantling institutionalised racism. With origins in the 1804 Haitian Revolution, black Haitian sovereignty was influential in slave abolition movements and decolonisation around the world.[22]

Huber’s ongoing poster work, Agassiz Down Under(2015–), also connects to this history of resistance by linking it to contemporary anti-racist movements in the United States. The posters use photos of a statue of Agassiz on the Stanford University campus that toppled over in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake—the statue appears comically planted headfirst into the tiled plaza like a javelin embedded in the ground. In each of the exhibited posters in the series, Huber declares solidarity with an African-American movement concurrent to the moment of the respective New Zealand exhibition, including the Charleston shooting in 2015, the Black Lives Matter protests in 2016 and the anti-racist protest victims in Charlottesville in 2017. Through these many works, Huber ʻunifies varied terrains’[23]—New Zealand, the United States, Switzerland and so on—following the trail of racism across the globe through the footsteps of one man whose legacy continues to be validated by states and institutions. In this sense, we could consider Huber as a type of time-travelling heroine, one who confronts the past in order to reconcile the present and to build a more altruistic future for our species—one that seeks kinship in all people.

Similar strategies can be found within the work of Darcell Apelu and John Vea. In Apelu’s Generation Exchange(2016), she invited people to join her on two separate walking tours. The first took place in the township of Patea, tracing the memories of her maternal grandparents and exchanging family stories and local knowledge with others; the second was in Auckland, from New Windsor Road to Mangere Lawn Cemetery, to trace the memories of her paternal grandparents. In both instances, Apelu employed the notion of a pilgrimage as a way to embody and share personal histories. This approach created a momentary forum through which members of the public felt comfortable in the act of exchange, finding commonalities in their own whakapapa.

Darcell Apelu, Generation Exchange (Patea), 2016. A walking tour of Patea, 6:00-8:00 am, 24 September 2016. Commissioned by Te Tuhi, Auckland. Photo by Bruce E. Phillips.

John Vea’s One Kiosk Many Exchanges (2016) also established a forum for sharing histories. He chose to respond to the entwined histories of the Emilia Maud Nixon Garden of Memories in Howick, Auckland. The garden was established by Nixon in 1962 to recognise the tangata whenua Ngāi Tai and the legacy of pioneering European women. Situated in the heart of Howick Village, the garden has dual Māori and colonial significance—as a site of Māori habitation for at least 300 years, and as land thought by the British to be strategic and which the military secured through occupation by the colonial Fencible soldiers. In more recent years, the garden has been a space of change, owing to a fire that damaged Te Whare o Torere and then later through the construction of a new building, Te Whare Matariki.[24] One Kiosk Many Exchanges sought to create an exchange with this history through a series of performative actions within a pop-up marquee in the garden. The title for the work borrows the Turkish term ʻkiosk’, a word originally used to describe an open pavilion-like building to gather under, but which was later used by Europeans to describe a space to serve or sell goods from. Vea brought this mixed understanding of the kiosk to the complex legacy of the gardens as a place of colonisation and community, of collapse and rebuilding, and of trauma and healing. Recognising that they were manuhiri to the garden and New Zealanders from many different cultural backgrounds, Vea and his collaborating artists[25] also explored what it meant to be visitors responding to a site of rich local significance. Over a number of weeks, the artists held regular wānanga with Taini Drummond, the kaitiaki taonga of the whare, to learn about the garden’s history and discuss shared notions of unity, temporality, permanence and precariousness that have further significance within the wider context of Auckland’s burgeoning population and growing housing shortage.

John Vea, One Kiosk Many Exchanges, 2016. In collaboration with Kaitiaki Taonga Taini Drummond and artists Valasi Leota-Seiuli, Sione Mafi, Newman Tumata and Jimmy Wulf. 12:00-1:00 pm, 8 October 2016. Emilia Maud Nixon Garden of Memories, 37 Uxbridge Road, Howick, Auckland. Photo Amy Weng.

Through their various strategies, artists Yu-Cheng Chou, Sasha Huber, Darcell Apelu and John Vea all establish moments of exchange by revealing that the past is enmeshed within the present. These artistic tactics share a resonance to the popular whakataukī ‘Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua’ (My past is my present is my future, I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past).[26] This proverb seems even more prescient today, as we become increasingly technologically connected via social media and more aware of how entwined our collective pasts really are. Alongside this knowledge, we have an ethical responsibility to share histories and bring them to light, but we also need to be cautious of the tendency to become too moralistic and overzealous or to ‘share’ too freely knowledge that we are not entitled to or do not have the rights to. It is important that we remember George Price’s revelation that humans will share with inherent self-interest, and that therefore the desire to ‘call out’ bias should be balanced with a questioning of one’s motivations. Perhaps by doing so—by recognising our commonalities and questioning our intent to share—we might be able to work towards more mutually beneficial economies of sharing as proposed by Lewis Hyde and to work towards Ashtosh Varshney’s notion of a deep-embedded mutual empathy.

CHEAT

As a social animal that depends upon the trust of others it seems a great contradiction that humans incessantly cheat each other. Cheating is an important aspect of our evolutionary biology and it can also be witnessed at many levels throughout nature. Think of the cuckoo bird, the craftiness of monkeys and parasites of all kinds. For humans, cheating can be a complicated thing to ethically rationalise because it manifests itself with positive and negative attributes. To cheat is to break the rules, to innovate and to challenge the status quo. At the same time cheating can disrupt progress, take advantage of others, encourage criminal activity and even lead to murder. The uncomfortable truth is that while many of us would be quick to label cheaters as ‘bad’ people, cheating is something that we are all complicit in perpetuating, and being able to refrain from cheating is not entirely due to stoic moral fibre but largely dependent on a given social context.

To understand this duplicitous aspect of cheating it is important that we first explore its innovative potential as an enabling aspect of democracy. For example, in the making of his work The Uprising (O Levante) (2012–13), Jonathas de Andrade convinced city officials in his hometown of Recife to allow him make a ‘fictional’ film, but his true intention was to hold the first horse-drawn cart race in the heart of the city.[27] Through this bureaucratic loophole, de Andrade was given an official licence, which he then handed back to the people to temporarily reclaim the city.[28] As a so-called ‘developing nation’, Brazil has been fast shifting to an urban-based economy—as part of this aspiration cities like Recife have banned all farm animals from the streets even though they represent a way of life established for centuries in such cities.[29] De Andrade explains that the legislation is more about controlling certain people in the urban environment than practical concerns: ‘it was neither about the animals nor the conditions of those workers, it was about cleaning any sign of backwardness from the town.’[30]

Jonathas de Andrade, O Levante, 2012-2013. Courtesy of Vermelho Gallery, Brazil.

After the event was staged, de Andrade invited an aboiador, João, to respond to it. An aboiador is a ‘singer from the countryside . . . [who creates] verses and rhymes for a given theme’ and the aboio ‘is the guide singing for the rider to lead a group of horses and bulls’.[31] In video documentation of The Uprising (O Levante) the aboiador’s lament drifts over the footage of carts hurtling through the streets and dwells on the constraint of the growing urban environment and the need to liberate the people. De Andrade’s work also demonstrates that cheating those in authority can be an important act of dissent rather than conformity. Art in this guise treads an ethically fine line to agitate power relations and enable the public to momentarily consider an alternative reality. This potential for disruption is championed by political theorist Chantal Mouffe in her proposition for agonistic democracy. Mouffe argues that there is an important distinction to be made between the ‘political’ and ‘politics’. The political is a ‘dimension of antagonism’ and is the ‘undecidability which pervades every order . . . where different hegemonic projects are confronted, without any possibility of final reconciliation’.[32] Politics by contrast is the rational organisation of the political which takes form as ʻthe ensemble of practices, discourses and institutions that seeks to establish a certain order and to organize human coexistence’.[33] Mouffe claims that liberal politics will always fall short of this aim due to its overreliance on rationality and its reductive emphasis on the individual as opposed to the perceived unresolvable chaos of the collective. Agonistic democracy, Mouffe contends, proposes a state of ʻconflictual consensus’:

A well-functioning democracy calls for a confrontation of democratic political positions. If this is missing, there is always the danger that this democratic confrontation will be replaced by confrontation between non-negotiable moral values or essentialist forms of identifications. Too much emphasis on consensus . . . leads to apathy and to a disaffection with political participation . . . While consensus is no doubt necessary, it must be accompanied by dissent.[34]

Mouffe’s theory of the political and antagonism also shares close similarities to philosopher Jacques Rancière’s definition of the political and dissensus, which he describes as a space of unresolved tension.[35] Both theories reinvestigate the meaning of democracy as a space not of consensus but of political contestation. Without it, we could not have healthy forms of dynamic civility where we sharpen each other through questioning and challenge. A similar challenge to the democratic use of urban space is apparent in Inhabitant (2011–14), a collaborative performance project by choreographer Sello Pesa, conceptual artist Vaughn Sadie & Ntsoana Contemporary Dance Theatre. This series of public happenings responded to the socio-political contexts of Newtown in Johannesburg, Dolapdere in Istanbul and the Mission District in San Francisco. All three performances featured the staging of a formal public speech complete with an entourage of dignitaries who arrived in slick black cars with tinted windows, public seating and a podium. After a somewhat delayed arrival, performers dressed in suits address the crowd with speeches appropriated from local politicians on topical local issues. In each example the speech takes place in a reality that is in direct contrast to the issues the speech purports to be solving. The establishment of the Brickfields Housing Development in Johannesburg is praised for introducing integrated affordable social housing yet the speech takes place in a distinctly dilapidated industrial zone. The Istanbul speech declares the opening of Dolapdere City Park as part of a programme to establish ‘a park for each neighbourhood’ but is juxtaposed against the setting of an awkward plaza that is dissected by two busy motorways. In San Francisco the speaker waxes lyrical about water shortages and an Urban Water Management Plan while talking on a site where the Mission River once flowed.

Their all-too-familiar promises seem to drift off into meaningless ramble as performers and city life divert attention. A helmeted man grooves and jives amongst the seated audience disrupting their personal space; a man on a bicycle penetrates the crowd at speed and encircles the neighbourhood; while another drags a 44-gallon drum over the pavement creating a cacophony of grinding sounds. Other performers playfully dodge traffic or dangerously roll across the road. With these satellite actions the performers test the social and built infrastructure of the cities by dissentingly affirming their autonomy or precariously conceding their control. In the San Francisco version, the police arrive, handcuff and carry off a man who is meandering around the neighbourhood and talking to himself.[36] The speakers continue unfazed by these interruptions, as if they and the public do not factor in the messages being announced. Inhabitantmuddles fiction and reality by operating in an unresolved realm that reinforces the realisation that our urban environs are as much socially controlled as are the physical barriers that tangibly define them. This surreal form of democratic contestation implores the public to question the power rituals that act to engender consensus by smoothing over complex issues.

Vaughn Sadie & Ntsoana Contemporary Dance Theatre, Inhabitant - Dolapdere, Istanbul,2011, (performance documentation).

Such social interventions embody a mixture of tactical and strategic artistic approaches similar to Trevor Paglen’s concept of ‘experimental geography’ which assesses how humans create and are in turn created by space.[37] Critic and curator Nato Thompson, who has worked closely with Paglen, describes experimental geography as a performative form of analysis . . . that brings the action of its process and the site of profound power into a relationship with each other . . . to think about power concretely, not just theoretically or abstractly. You can walk downtown and see a battle taking place.[38]

Using the ability of art to disrupt social order, to cheat the system and thereby reveal systems of power was also deployed by the movement YOUAREHEREWEAREHERE in a series of social interventions. Rather than taking to the streets, this ambiguous anonymous group targeted the institutional rituals that frame socially engaged art—choosing to disrupt the proceedings and marketing of the Share/Cheat/Unite exhibition. At the exhibition opening the group convinced academic Dr Peter Shand[39] to deliver a nonsensical speech filled with repetitious personal anecdotes that endlessly promised insight but refused to deliver. The group also commandeered Te Tuhi’s social media accounts flooding the organisation’s feeds with memes—a prancing puppy gif is labelled with the slogan ‘working for you’, an image of a screaming baby is paired with the title ‘IT’S COMING’. During a local art festival[40] YOUAREHEREWEAREHERE also staged a dada-like raffle. The raffle prize was a worthless widget—a wooden doughnut-shaped object accompanied by an elaborate user’s manual. These interventions humorously toyed with the increasing pressure on artists and art organisations to prove their worth to society within an economy of attention by producing ‘positive’ social experiences for the public.

However, the social benefits of creating agonistic moments of contested democracy is only one dimension in which cheating manifests within art and society. At its simplest, cheating is used as a last resort in order to survive. A person in a survival situation may have little option but to do things that most people would find amoral or even consider evil. To understand this murky moral quandary it is necessary to exit political theory and delve into social psychology and in particular Stanley Milgram’s 1961 obedience study. Influenced by the trial of Nazi Adolf Eichmann, Milgram was motivated to understand how ‘ordinary people are capable of extraordinary cruelty’.[41] In his study Milgram asked the subjects to administer electric shocks to another person (an actor) if they got an answer wrong. The study consisted of many experimental permutations. Each change to the experiment had corresponding variables ranging from 0% to 65% compliance in the subjects’ willingness to dispense doses of pain to another person. Overall it was found that given the right circumstance the majority of people would continue to shock the fictitious victim even until there was no response. The study discovered that rather than blindly following orders the majority of us will inflict pain on another only if we believe we are making an important contribution to society or if we feel we have no other choice.[42]

Social psychologist Philip Zimbardo, who has conducted similar experiments, explains that it is social context rather than individual character that is the defining contributor:

Most of us can undergo significant character transformations when we are caught up in the crucible of social forces . . . what we imagine we would do when we are outside of that crucible may bear little resemblance to who we become and what we are capable of doing once we are inside its network.[43]

The influence of society as a ‘crucible of social forces’ is clearly apparent in Testimonio(2012) by artist Aníbal López (A-1 53167) who invited a sicario (contract killer) to give a public talk as part of dOCUMENTA 13. Talking from behind a backlit screen, the anonymous sicario explains that he has been entrapped within a cycle of violence since he was twelve years old but that he is now studying law so that he might have a future beyond killing. He clarifies that in the corrupt societal context of Guatemala it is the army that commissions him to do the jobs that they cannot legally do. ‘I am paid to make a social cleaning . . . my job is to find people and make them disappear,’ he says, after explaining that he has indiscriminately killed men, women and children—his first being a woman whom he stabbed fifty times.[44] In a matter-of-fact tone, he clarifies:

We don’t really have a heart anymore. What life did to us turned our hearts to stone . . . we do it because it is a necessity but we get used to it . . . you cannot work there legally and honestly. If you don’t have a job, you are forced to turn to crime, to become a criminal.[45]

Aníbal López (A-1 53167), Testimonio, 2012 (video still) video, color, sound, 43:39 min. Courtesy of Prometeo Gallery, Italy.

In the extensive question session that follows, the audience draw out further information from him:

Are your murders clean or bloody and torturous?

‘We cut the skin of the people . . . I hang people . . . it’s hard if they suffer but it is the work and we have to do it.’

Are there any limits for you?

‘No, we don’t have any limits.’

When someone dies do you perceive any energy changes?

‘We don’t work with feelings . . . we are very professional.’

Do you believe in God?

‘I believe in what I see and nothing else.’

Do you take pills to sleep?

‘No nothing, sometimes liquor.’

Do your victims follow you into your dreams?

‘Yes of course . . . there are some that curse you.’

How many people have you killed?

‘More than 26.’[46]

With each question the audience’s body language is giddy with nervous smiles or troubled with stone-faced expressions—all of which reveal their own morals, preconceptions, naivety and inability to understand an entirely different socio-political context. In response, the sicario answers in an unemotional and nonchalant way. In both the live and recorded experiences of the work, what becomes apparent is that the event is about people confronting what Hannah Arendt famously described as the ‘banality of evil’ in which implausible horrors can performed by ‘normal’ people.[47] López’s work is hard to confront because it challenges the traditional expectation we have of art that it be an instructional influence. In discussing the politics of representing suffering, Susan Sontag explains that the moral expectation of art to instruct stems from religious and political legacies.[48] For example, the horrific suffering of Christ on the cross becomes a promise for eternal life if we follow his teachings. According to Sontag, such moralistic representations of suffering are deemed acceptable because they are the ‘product of wrath, divine or human . . . intended to move and excite, and to instruct and exemplify’.[49] In contrast, there is no explicit moral agenda at play in López’s work, just the ethical provocation that this man is not an evil monster but a human stuck in a specific situation.

López and other artists often labelled as controversial, such as Santiago Sierra, have been accused of using humans as the medium for their art, which they then profit from.[50] By establishing direct encounters between people, such artists do away with the fiction of art and provide a real experience. Through this, they make us aware that we[51] are unsafe within our own skin and in so doing issue a challenge to reflect ‘on how our privileges are located on the same map as their suffering . . . [for] the wealth of some may imply the destitution of others’.[52] Upon consideration of this discomfort we might come to the same conclusion as Zimbardo, that we can challenge and change such negative situational forces only by recognizing their potential power to ‘infect us,’ . . . Any deed that any human being has ever committed, however horrible, is possible for any of us . . . that knowledge does not excuse evil; rather, it democratizes it, sharing its blame among ordinary actors rather than declaring it the province only of deviants and despots—of Them but not Us.[53]

Unite

The most memorable thing I learnt at high school was the fear of pack mentality. Especially one day, when a group of about thirty teenage boys surrounded me and five of my friends. It was only one or two who seemed to be leading the group. A small minority, who orchestrated the swarm of bodies to kick, punch and wrestle us into submission. Afterwards we were rattled and physically bruised yet something else had changed, something that could not be taken back.

It was only a schoolyard incident, and barely registers on a scale of trauma. Still this experience has been indelible enough to make me feel uncomfortable in large groups of people—for fear of their ability to turn on individuals at a whim. Rationally, I concede, there are obvious evolutionary advantages to forming groups. They give us safety, enable us to create infrastructures and they give us a sense of belonging – but how exactly do we form groups and why do we use them to vie for power?

According to social psychologists, group formation is influenced by something called emotional contagion—which is basically the unconscious phenomenon of physically mirroring other people’s emotions. A 1966 experiment at the University of Pittsburgh revealed that within 21 milliseconds of meeting someone we will mimic their emotional state through minute adjustments to our body language and facial expressions.[54] Other studies have shown that this subtle mirroring allows us to actually physically feel what others are feeling. One such study was conducted by social psychologists Howard Friedman and Ronald Riggo in 1981 by getting groups of people to sit silently together for only two minutes.[55] Even after this short period of time, the subjects showed evidence of reflecting each other’s emotional states.

Emotional connection is what enables us to unify and co-operate with others. This highlights the fact that our own emotional state is to some degree dependent on those whom we share our time with. When we unite we are emotionally bound to each other and we will protect this sense of unity sometimes at great cost to those outside the group. For groups are defined not only by what unifies them, but also by who or what is determined different and therefore outside the group.[56] Emotional contagion is an extremely positive human attribute as it aids our collective survival but it is also unavoidably negative because it demands conformity and makes us creatures prone to manipulation. All because we desire to belong—we hunger to be part of something larger.

The power of emotional contagion and our proclivity towards groupthink is a key driver behind Mark Harvey’s participatory performance Turquoisation: For the coming storm (2016). Together with a troupe of turquoise-garbed performers, Harvey infiltrated the Share/Cheat/Uniteexhibition opening, paraded down busy streets in downtown Auckland and seamlessly merged with the carnivalesque atmosphere of a community art festival.[57] In each iteration, the group slipped between strategies of religious evangelism, corporatised mindfulness, cult-like unity and neo-liberal positivity. ‘Follow’ chants the instructional video, as the performers convince members of the public to join them in repeating facial expressions and body actions. While ridiculous fun, these repetitious requests have an exploitative agenda—to make us suspend critical thought and to be mindlessly directed by others.

Mark Harvey, Turquoisation: For the coming storm, 2016. Instructional video and series of public interventions, filmed by Daniel Strang, performers: Sara Cowdell, Lisa Greenfield, Mark Harvey, Kristian Larsen, Ivan Mršić, Claire O'Neil, Adrian Smith, Val Smith and Chancy Rattanong. Commissioned by Te Tuhi, Auckland. Photo By Amy Weng.

However, simple emotional contagion is not to be confused with the pop culture understanding of brainwashing that occurs only under situations of extreme coercion.[58] Nor should it be confused with the fiction of crowd control. This dubious notion of the mindless multitude was popularised after the French revolution by the social scientist Gustave Le Bon through his 1896 book The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. Claiming that the crowd held some unknown ‘magnetic’ ability, he wrote:

an individual immersed for some length of time in a crowd soon finds himself . . . in a special state, which much resembles the state of fascination in which the hypnotized individual finds himself in the hands of the hypnotizer . . . An individual in a crowd is a grain of sand amid other grains of sand, which the wind stirs up at will.[59]

Here Le Bon describes crowds not as many free-thinking individuals but a mass of mindless automatons that are easily manipulated and required to be controlled by those in power. Again he writes:

Crowds are only powerful for destruction . . . crowds act like those microbes which hasten the dissolution of enfeebled or dead bodies. When the structure of a civilisation is rotten, it is always the masses that bring about its downfall.[60]

Social psychologists have more recently learned that crowd behaviour is not as mindless as Le Bon thought.[61] What defines a crowd and how it might react is predicated on the situation. In disaster scenarios, for example, the common myth is that the societal fabric collapses, people go mad and lawlessness abounds. Yet research conducted by social psychologists such as John Drury indicate that in those situations people actually form tighter bonds and look out for each other with a common aim to survive—something that Drury terms collective resilience.[62]

Despite these findings, Le Bon’s myth of the mindless crowd still persists. For example, when Hurricane Katrina hit there were many spurious reports of lawlessness occurring in the Superdome, except this did not actually occur. TheNew York Timeslater stated that these were racially motivated reports, ‘built largely on rumours and half-baked anecdotes’ and which ‘quickly hardened into a kind of ugly consensus: poor blacks and looters were murdering innocents and terrorizing whoever crossed their path in the dark, unprotected city’.[63] Similarly the Guardianlater published an article stating that ‘Journalists on the ground were often fiercely empathic and right on the mark, but those at a remove were all too willing to believe the usual tsunami of clichés about disaster and human nature.’[64] In addition, philosopher Slavoj Žižek points out, these faulty reports had real ‘material effects’ that ‘generated fears that led the authorities to change troop deployments’ and ‘delayed medical evacuations’, all of which fuelled a type of ‘pathological condition’.[65]

Le Bon’s damaging influence also encourages the condemnation of protest situations that erupt into disorder. Again, researchers such as John Drury have revealed that these are not due to mindless crowd behaviour playing out, but are a reaction to how the group might be treated by the police.[66] If there is a perceived disproportionate reaction given from the police then of course the crowd will react. Later, however, they will be demonised by certain political actors.

It is imperative that we question the perspective by which we come to understand the multitude. Who is telling us that the crowd is something to fear? Le Bon’s theories were written with the aim of demonising the public to popularise the opinion that those in power should use control tactics to manipulate the population to service their own ends. A key tool in this political control was Le Bon’s influential analysis of speeches which gave rise to the following formula: make affirmative truth claims, repeat a message until it becomes contagious, use exaggerated statements, use symbols and metaphor to trigger the imagination, avoid reasoning and logic and lastly use ill-defined abstract words. I find this last one the most unnerving of Le Bon’s techniques. He writes:

for example . . . the terms democracy, socialism, equality, liberty . . . whose meaning is so vague that bulky volumes do not suffice to precisely fix it. Yet it is certain that a truly magical power is attached to those short syllables, as if they contained the solution of all problems. They synthesise the most diverse unconscious aspirations and the hope of their realisation.[67]

Hu Xiangqian, Speech at the edge of the world, 2014 (video still) single channel HD video, 12:31 min. Courtesy of Long March Space, Beijing.

We have all heard this oratory structure implemented. It underlies all of the most powerful speeches over the last hundred years or more, from Winston Churchill and Adolf Hitler through to Martin Luther King Jr, Margaret Thatcher, Barack Obama and Donald Trump. It is vital to point out that the power of this formula is not in its brainwashing but in its strategic deception, and that the same tools used to manipulate can also be used to liberate. This is the basis for Hu Xiangqian’s work Speech at the edge of the world (2014), in which he returns to his hometown of Leizhou—a small rural town located at the tip of a peninsula on the southwest coast of China. Using Le Bon’s strategies, Xiangqian addresses an assembly of teenage school students. Xiangqian’s speech is rich in visual metaphor and language that emphasises collective unity whilst inspiring the students to overcome the parochial limitations on their lives. He inspires them to become self-educated, to understand the wealth of opportunities that are available and to understand that they are not cut off from the world but connected. Xiangqian’s animated performance is sincerely heartfelt but he also knowingly performs the cliché persona of the motivational speaker and local boy made good. Typical of their age, the students seem to remain bored, indifferent and apathetic to Xiangqian’s slick presentation. The children know the drill; they are bound by the rules placed upon them by the definition of being pupils and they just have to bide their time for the speech to end.

The deliberate irony of Xiangqian’s work illustrates that the body politic is an arbitrary distinction that nevertheless controls us. As theorist Judith Butler explains in her text Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly:

‘The people’ are not a given population, but are rather constituted by the lines of demarcation that we implicitly or explicitly establish . . . there is no possibility of ‘the people’ without a discursive border drawn somewhere.[68]

This means that whatever mode in which ‘unity’ is created—be it through emotional contagion, fear-driven rhetoric of the crowd or the persuasive trick of oratory—it will always act to exclude. Through exclusion comes dehumanisation, which renders states of precariousness and excuses forms of violence. Following Butler’s logic, it seems essential that artists act not as solitary individuals but practitioners who are cognisant of the social and political contexts in which they work. As Butler again illuminates:

The exercise of freedom is something that does not come from you or from me, but from what is between us . . . the body is less an entity than a living set of relations; the body cannot be fully dissociated from the infrastructural and environmental conditions of its living and acting.[69]

Butler’s argument shares some strong resemblances to indigenous perspectives such as the Kaupapa Māori approach of whakawhanaungatanga—a way in which people can come into a meta-relationship with each other, space, time and the natural environment.[70] From this perspective, in which the individual is located within a larger kinship framework, humans become viewed as part of a political ecology.[71] As the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy writes, ‘one cannot make a world with simple atoms . . . There has to be an inclination or an inclining from one toward the other, of one by the other, or from one to the other.’[72]

Butler warns that if we do not uphold the understanding that society is bound to a set of living relations, ʻthe human as an agentic creative’ cannot emerge to generate a plurality of embodied action.[73] I understand this to mean that diversity in society cannot truly flourish until we shift thinking away from an individual paradigm to one that values our connective relations. Thus, as a form of resistance, there is great power in diverse bodies and voices uniting together in public space. To publicly unite in a plural form is to exercise freedom, to have the right of appearance and to say, in the simplest way, that ‘we’ exist.

These notions of plural embodied action are present in Ivan Mršić’s work Kakokarangaphonia Orchestra (2016). This one-hour orchestra formed for the first and only time on a Saturday afternoon at Auckland’s Karanga Plaza. It comprised 23 people, including musicians, sound artists and untrained enthusiasts. They assembled armed with brass, strings, bits of scrap plastic, tubes, bowls, a handsaw and strange contraptions made of hacked electronic hardware.

Ivan Mršić, Kakokarangaphonia Orchestra, 2016. A collaborative offsite performance, 12pm - 1pm, 15 October 2016, Karanga Plaza, Wynyard Quarter, Auckland. Commissioned by Te Tuhi, Auckland. Photo by Bruce E. Phillips

In the spirit of the orchestra’s name—a combination of the Greek word kako(bad or unpleasant) and the Māori word karanga(a ceremonial welcome, or to call out)—they opened not with their ramshackle instruments but with a collective wailing that sounded like a haunted many-voiced wind—an apt way to signal their collective bodily presence and an indication that they were not going to follow any conventional orderly conduct. This experimental sound ensemble was invited to respond to a random composition of numerical code, which Mršić communicated to the performers through cards held above his head. As a celebration of unbridled sonic expression and movement, the adherence to these fluxus-like instructions was very loose if not ignored entirely. The result was an unruly event that was part rough sound, part protest and part jungle-like chorus.

By creating a space of communal potential, the Kakokarangaphonia Orchestra was an acknowledgement of the complex nature that sound plays in our social encounters as a vehicle for unity, discord or ingenuity. It was also an attempt to gain insight into the fact that society is not always rational and ordered but rather a patchwork of chance encounters and serendipitous symphony. At its core, Kakokarangaphonia Orchestra was an opportunity to exercise the privilege and freedom permitted in Aotearoa New Zealand—the right to congregate as a diverse assemblage of people and get lost in concert with one another.

To be human is to have the freedom of being part of something larger than the individual. The great challenge for society is to uphold this human right without limiting agency or allowing violence to threaten the lives of its citizens. Crucial to this social contract is acknowledging that we are all assigned to one another in a reciprocal bond—an uncomfortable fact that reveals how vulnerable we actually are. Discussion of this sentiment is how Butler concludes her Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly: it is ‘our shared exposure to precarity’, she says, that holds the potential for recognising our equality.[74]

[1]Lewis Hyde, The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World, 25th anniversary edition (New York: Vintage, 2007), 12.

[2]Hyde, The Gift.

[3]Hyde, The Gift.

[4]Hyde, The Gift, 205–6.

[5]Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene, 2nd edition (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

[6]Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex(New York: A.L. Burt, 1874), 71–72.

[7]Oren Harman, The Price of Altruism: George Price and the Search for the Origins of Kindness(New York, N.Y.: W. W. Norton & Company, 2011), 208.

[8]Michael Bond, The Power of Others: Peer Pressure, Groupthink, and How the People Around Us Shape Everything We Do(London: Oneworld Publications, 2015), xiv.

[9]Harman, The Price of Altruism.

[10]Examples of this could include the Labour supporters confounded at the outcome of the 2014 New Zealand election, those mystified by the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom and, in the United States, Donald Trump’s ascension to the White House which many thought was an impossibility.

[11]Bond, The Power of Others, 191.An obvious example of this is the ‘You will not replace us’ chants used by the alt-right and neo-Nazi groups that marched en masse in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, claiming to be disenfranchised by multiculturalism.

[12]Ashutosh Varshney, ‘Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Rationality,’in Peace Studies: Critical Concepts in Political Science, ed. Matthew Evangelista (Taylor & Francis, 2005).

[13]Varshney, ‘Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Rationality,’3.

[14]Suzana Milevska, ‘Lunar Geological Map of Racism: On Racism and Slavery as Addressed in Sasha Huber’s Rentyhorn,’in Rentyhorn, ed. Huber (Helsinki: Kiasma, 2010).

[15]Derek Grzelewski, ‘Glaciers—Ice on the Move,’New Zealand Geographic, www.nzgeo.com/stories/glaciers-ice-on-the-move/ (accessed 10 November 2017).

[16]Hans Barth, ‘Louis Agassiz and Adolf Hitler: Documents of Racist Mania,’in Rentyhorn, ed. Sasha Huber (Helsinki: Kiasma, 2010).

[17]Sasha Huber, Rentyhorn (2008), video, 4:30 min.

[18]Sasha Huber, Louis Who? What you should know about Louis Agassiz. Intervention, Praça Agassiz, Rio de Janeiro(2010), video, 3:50 min.

[19]Also known as Te Tai o Wawe.

[20]Sasha Huber, Karakia—The Resetting Ceremony(2015), video, 5:20 min.

[21]In the making of this artwork Sasha Huber was in contact with Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu officials who provided guidance and contact with Jeff Mahuika, a pounamu carver local to the glacier. In addition, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu in collaboration with Makawhio Rūnanga ‘proposed supporting research on new and appropriate Māori place names for the “Agassiz Glacier” and another South Island feature, the “Agassiz Range”, as there are currently no known Ngāi Tahu names for these landmarks.’ See Sasha Huber, ‘Karakia—The Resetting Ceremony,’2015, www.sashahuber.com/?cat=10046&lang=fi&mstr=4.

[22]Barth, ‘Louis Agassiz and Adolf Hitler: Documents of Racist Mania.’

[23]Pirkko Siitari, ‘The Name of a Mountain,’in Rentyhorn, ed. Sasha Huber (Helsinki: Kiasma, 2010).Siitari also writes that Huber ‘raises local themes, but they reflect broader, transnational issues and ideologies’.

[24]‘Wharenui Built in Howick Is Burnt Down Marae Investigates,’Marae(TV ONE, n.d.), www.youtube.com/watch?v=m5XufbofBkU; Simon Smith and Scott Morgan, ‘Education in New Whare,’Eastern Courier, 26 March 2014, www.stuff.co.nz/auckland/local-news/eastern-courier/9864538/Education-in-new-whare;‘Council Accepts Withdrawal of Name for Whare,’Scoop News, 23 July 2007, www.scoop.co.nz/stories/AK0707/S00253.htm (accessed 10 July 2016).Bruce E. Phillips et al., What Do You Mean, We?, ed. Rebecca Lal (Auckland, NZ: Te Tuhi, 2012).

[25]John Vea collaborated with artists Valasi Leota-Seiuli, Sione Mafi, Newman Tumata and Jimmy Wulf.

[26]Sidney M. Mead and June Te Rina Mead, People of the Land: Images and Māori Proverbs of Aotearoa New Zealand(Wellington: Huia, 2010).

[27]Jessica Morgan, Gwangju Biennale 2014: Burning Down the House, Tra edition (Bologna, Italy: Damiani, 2014); Jonathas de Andrade, ‘Jonathas de Andrade “The Uprising”,’ Vdrome, 2014, www.vdrome.org/jonathas-de-andrade-the-uprising/; ‘Jonathas de Andrade. The Uprising (O Levante). 2013 | MoMA,’ The Museum of Modern Art, 2017, www.moma.org/collection/works/190986.

[28]Andrade, ‘Jonathas de Andrade “The Uprising”.’

[29]Morgan, Gwangju Biennale 2014; Andrade, ‘Jonathas de Andrade “The Uprising”’; ‘Jonathas de Andrade. The Uprising (O Levante). 2013 | MoMA.’

[30]Andrade, ‘Jonathas de Andrade “The Uprising”.’

[31]Ibid.

[32]Chantal Mouffe, Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically, 1st edition (London/New York: Verso, 2013), 2.

[33]Mouffe, Agonistics,3.

[34]Mouffe, Agonistics,7–8.

[35]Jacques Rancière, Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics, ed. Steven Corcoran (London/New York: Continuum, n.d.).

[36]This man, made visible through the documentation of the performance, was not officially involved in the performance but was acting equally unusual as the performers who were left undisturbed by the police.

[37]Paglen is influenced by the science of geography but also draws on insights from Henri Lefebvre and Walter Benjamin who both position the politics of lived experience within actual physical space.

[38]Nato Thompson, Seeing Power: Art and Activism in the Twenty-First Century(Melville House, 2015), 158–9.

[39]Head of Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland, and Te Tuhi board member.[40]1:15–5:00 pm, 22 October 2016, outside Salvation Kitchen, 1843 Great North Road, Avondale, Auckland, as part of the 2016 Whau Arts Festival: Twenty Whau Seven.

[41] Michael Bond, The Power of Others: Peer Pressure, Groupthink, and How the People Around Us Shape Everything We Do(London: Oneworld Publications, 2015), 68.

[42]Bond, The Power of Others.

[43]Philip Zimbardo, The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil, reprint edition (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2008), 211.

[44]Aníbal López (A-1 53167), Testimonio(2012), video, colour, sound, 43:39 min. Courtesy of Prometeo Gallery, Italy.

[45]Ibid.

[46]Ibid.

[47]Hannah Arendt and Amos Elon, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, 1st edition (New York, N.Y: Penguin Classics, 2006).

[48]Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, new edition (London/New York/Victoria: Penguin, 2004), 37.

[49]Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others,36.

[50]Tirdad Zolghadr, ‘Them and Us,’ Frieze, 2006, https://frieze.com/article/them-and-us.

[51]By ‘us’ and ‘we’ I mean all people who might encounter such artworks and not some privileged audience.

[52]Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 92.

[53]Zimbardo, The Lucifer Effect, 211.

[54]Michael Bond, The Power of Others: Peer Pressure, Groupthink, and How the People Around Us Shape Everything We Do(London: Oneworld Publications), 2015 8.

[55]Howard S. Friedman and Ronald E. Riggio, ‘Effect of Individual Differences in Nonverbal Expressiveness on Transmission of Emotion,’Journal of Nonverbal Behavior6, no. 2 (1 December 1981), 96–104, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00987285; Bond, The Power of Others.

[56]Bond, The Power of Others.

[57]Mark Harvey’s Turquoisation: For the coming stormwas performed at various locations and times in October 2016: 5–8 pm, Wednesday 12 October 2016 (in collaboration with Kraken Crumpets as part of Street ArtDego and Artweek Auckland), Upper Khartoum Place, Auckland CBD; 1–3 pm, Sunday 16 October 2016, roaming on Queen Street and other locations, Auckland CBD; 5:30–8:30 pm, Friday 21 October 2016, as part of the 2016 Whau Arts Festival: Twenty Whau Seven, held at 1875 Great North Road, Avondale, Auckland.

[58]Kathleen Taylor, Brainwashing: The Science of Thought Control(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[59]Gustave Le Bon, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind(Macmillan, 1896), 13.

[60]Le Bon, The Crowd, xix–xx.

[61]Bond, The Power of Others, 30.

[62]John Drury, David Novelli, and Clifford Stott, ‘Managing to Avert Disaster: Explaining Collective Resilience at an Outdoor Music Event,’European Journal of Social Psychology45, no. 4 (June 2015), 533–47.

[63]Trymaine Lee, ‘Tales of Post-Katrina Violence Go From Rumor to Fact,’The New York Times, 26 August 2010, www.nytimes.com/2010/08/27/us/27racial.html.

[64]Rebecca Solnit, ‘Four Years On, Katrina Remains Cursed by Rumour, Cliche, Lies and Racism,’The Guardian, 25 August 2009, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2009/aug/26/katrina-racism-us-media.

[65]Slavoj Žižek, By Slavoj Žižek—Violence(Picador, 2009), 84.

[66]Roger Ball and John Drury, ‘Representing the Riots: The (Mis)use of Statistics to Sustain Ideological Explanation,’Radical Statistics106 (2012), 4–21; Clifford Stott and John Drury, ‘Contemporary Understanding of Riots: Classical Crowd Psychology, Ideology and the Social Identity Approach,’Public Understanding of Science26, no. 1 (1 April 2016), 2–14.

[67]Le Bon, The Crowd, 100.

[68]Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly(Cambridge, Mass. / London: Harvard University Press, 2015), 3–5.

[69]Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly,52–65.

[70]Russell Bishop, Freeing Ourselves(Rotterdam / Boston: Sense Publishers, 2011); Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples(Zed Books, 1999).[71]Emilie Rākete, ‘In Human Parasites, Posthumanism, and Papatūānuku,’in The Documenta 14 Reader, ed. Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (München / London / New York: Prestel, 2017)

[72]Jean-Luc Nancy, The Inoperative Community(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991), 3.

[73]Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, 44.

[74]Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly,218.