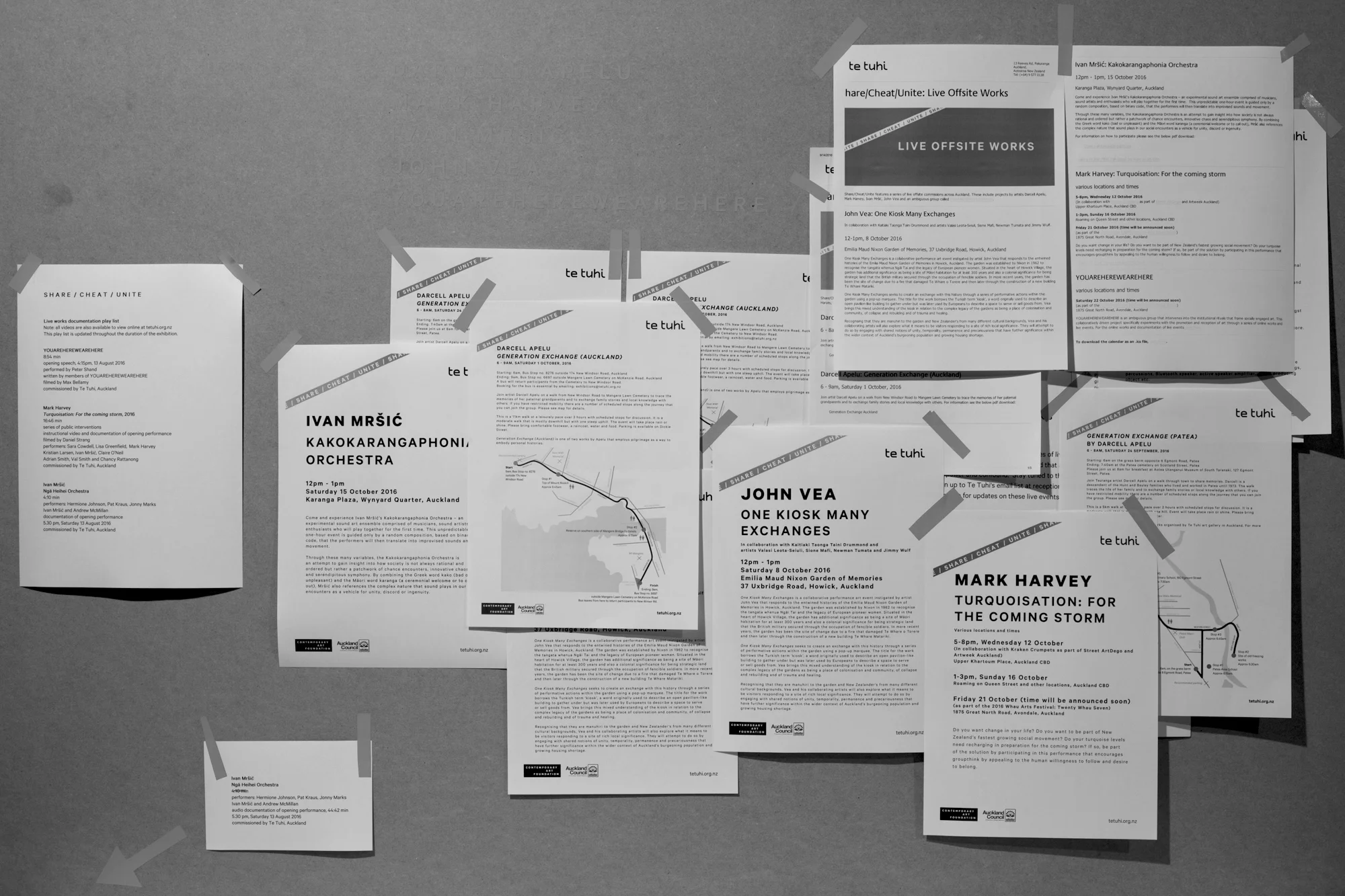

Generation Exchange

Darcell Apelu, Generation Exchange (Patea), 2016

a walking tour of Patea, 6:00-8:00 am, 24 September 2016, photo Amy Weng.

PUBLISHED IN:

SHARE/CHEAT/UNITE VOL.1

TE TUHI, AUCKLAND

2017-2018

READ THE EBOOK HERE: VOLUME 1

Darcell Apelu’s Generation Exchange (2016) consisted of two separate walking tours. The first took place in the township of Patea, to trace the memories of her maternal grandparents and to exchange family stories and local knowledge with others; the second was held in Auckland from New Windsor Road to Mangere Lawn Cemetery, tracing the memories of her paternal grandparents. The following is an edited conversation reflecting on the project between Darcell Apelu and Bruce E. Phillips that took place over a year later.

Bruce E. Phillips: Now that a bit of time has lapsed, what are your thoughts about the project?

Darcell Apelu: I have become more aware that my connection to these sites is complicated. I feel connected through family memories, but because I do not live at either location I don’t have full permission or access to the histories or current issues of these places. As much as I try I will never get to that point of truly knowing or truly connecting. I have only understood this by going through the process of producing the work. This realisation is possibly something that happens for a lot of people who are trying to connect with their past or their culture—in some way you will never fully encapsulate what that lost connection means.

B: In both walks we started with a house—the home of your mother’s family in Patea and the home of your father’s family in Auckland. Why was that important?

D: For me it initially came from looking at Dad’s old family home and being able to relate easily to that space because I spent some of my childhood there. We also have a tradition in our family that we often revisit these houses just to check what changes have been made. It was an important starting point because it was a source of pride—a pride in me being able to know that this is the space where my father grew up and that my father had an awesome upbringing even with all the difficulties of being a Pacific Island kid in the 1960s with the resilience that they had to have. That is why I wanted to start with the homes of my parents because they embody a sense of belonging and pride, even though my family no longer owns these houses.

Because I don’t have memories of my own of the Patea house, I had to channel my mum to describe the significance of it because she was the one who had passed on that whole history to me. It was the home of my maternal grandparents Dorothy and Trevor and that was my mother’s first home that she lived in with her two brothers. But the house has changed a lot now. Rather than a family home it is used as a holiday home. The front door has been moved from the front to the side because they have added a deck and decorated it in a seaside theme.

B: Both walks concluded at the cemeteries where your father’s and mother’s families are buried. Rather than being morbid or too personal, this actually became an affecting contribution to the work.

D: When I think of a cemetery I never think of a sad place, I think of a place of happiness and a place to be reflective and of knowing. Whenever I am in Taranaki I will make the effort to visit the cemetery in Patea and it is never a chore to just be in that place. It is the same when I am in Auckland. If I am passing through the area I will just visit—even only for a few minutes for reflection. It doesn’t have to be this drawn-out thing—it can be a quick hello. The cemetery is a place that holds significance beyond any one individual person—being in that place means to be beyond you. How can I describe it? It is not an out-of-body sensation but something similar. In the contemplative space of the burial ground you become part of something more than yourself.

Darcell Apelu, Generation Exchange (Patea), 2016

a walking tour of Patea, 6:00-8:00 am, 24 September 2016, photo by Bruce E. Phillips.

Darcell Apelu, Generation Exchange (Patea), 2016

a walking tour of Patea, 6:00-8:00 am, 24 September 2016, photo by Bruce E. Phillips.

B: So these locations become nodes or prompts for you to share family memories—memories that are also mostly new to you. Starting with part one in Patea, could you talk about each of those locations and the memories attached to them?

D: After visiting your mum’s childhood home we walked around the corner to a school. This was the first of two schools we visited in Patea. This school was originally the high school, but is now the Patea Area School that currently holds only 40 students from ages five to high school age. I used this space as a memorable location because my mother was only at this school for one year due to the family moving to Tauranga—so it is a significant site because it is the place of departure and change. It was during this time that my grandfather left the freezing works—the freezing works was on the downturn and its eventual closure would have a significant effect on the town. He ended up getting a contract to manage the Anchor Inn, which was a tavern owned by Lion Breweries. He saw this career shift as a way to give the kids more opportunities. And it did. Their move to Tauranga became a pivotal part of my mother’s upbringing.

From the school we then walked down the hill and across a bridge to the site of the old freezing works. I come from a long line of freezing works workers. My mother’s father and his father and my father also worked in the industry. This lineage of blue-collar workers is really interesting for me. It made me aware of how fortunate and privileged I am that my parents and my parents’ parents had created stepping-stones that have allowed my generation to pursue whatever we wanted in life.

B: The legacy of working-class labour is a tangible gift that you have inherited—energy that has been vested in your future. That realisation is really profound in terms of ‘generation exchange’.

D: Being grateful for what you have and recognising what others have given you is so important. It is a small thing that is easily taken for granted. The site of the freezing works is also the source of other stories—work stories. I shared the tale of my grandfather’s workmate who got a meat hook impaled through his hand. Health and safety and OSH wasn’t around in those days, there was no chainmail gloves or other protective gear. Everything was done by hand and this man was just lifting a carcass onto a meat hook but rather than barbing the carcass, the hook went right through his hand.

B: After the freezing works we backtracked our steps back to the bridge where we looked over the river. Your great-uncle Bruce shared a memory.

D: Yes, a sad memory of his little brother Morris. Morris was the second to youngest in the family and one day they were playing on the wharf by the river and while Morris was climbing down one of the ladders he slipped, knocked his head and went under the water and unfortunately drowned. They didn’t find him till a couple of days later, when he washed up on the beach further downstream. I was surprised at how forthcoming Uncle Bruce was to share a deeply sad personal story with a bunch of strangers. Later on, I discussed it with my mother and we looked into the dates of the incident and confirmed that the day after Morris died my grandmother had given birth to the youngest boy. So within a 48-hour time span my grandmother had lost one son and gave birth to another.

B: From there we walked to the site of the old primary school.

D: I shared some school photos of my mother and her sisters. The school has since closed but it remains for me as a kind of imaginative space where I can stand there and envisage the things my great-grandmother, my grandmother and my mother would have gotten up to as children. Being able to visit these places is really important to me, because through them I can trace back through multiple generations and see how I am connected to something larger. We then walked to the cemetery where we visited my mother’s family members that are buried there, and connected to the graves of people who featured in the stories that had been shared, such as Morris and my grandmother.

Darcell Apelu, Generation Exchange (Patea), 2016

a walking tour of Patea, 6:00-8:00 am, 24 September 2016, photo by Bruce E. Phillips.

Darcell Apelu, Generation Exchange (Auckland), 2016

a walking tour from New Windsor Road to Mangere Lawn Cemetery, 6:00-9:00 am, 1 October 2016

photo by Amy Weng

B: A few weeks later we were in Auckland for part two of Generation Exchange.

D: This was a much longer walk and was a significantly different experience. It was raining and it was a dark morning because of the clouds. We met at New Windsor Road outside the house my father grew up in. Here I talked about the migration of my grandparents—moving from Niue and arriving at this home—and my father’s childhood and discussed the significance of the journeys within the stories.

I also talked about my grandfather, who had to walk every day over 20 kilometres from that house to the wharf in Auckland and then home again. Everything that my father’s family did involved walking long distances—it was their primary mode of transport. Some of the participants on the day also shared their own family stories of the ‘old Auckland’. It was an Auckland that was experienced via walking rather than driving—a perspective that is so foreign to us today.

My father’s family stories of walking are what originally inspired me to create an artwork that involved walking as a primary mode to connect with these memories. He would always say how far he would walk and how we [his children] don’t do much walking. He was constantly making these observations and reflecting on where he was in life—I felt I was lucky enough to hear that and to understand that.

From the house we walked to the top of Mount Roskill, where we could look out on to the city but in particular to look towards War Memorial Park on May Road where earlier that year [in April 2016] a large plaque and flagpole was installed that commemorates the names of 150 Niueans who fought in the First World War. My grandfather was one of these men. His participation in the war was part of the story of how he immigrated to Aotearoa New Zealand.

A lot of Niuean soldiers came from Niue to New Zealand for training and then to the war. A lot of them were essentially not there to fight but to dig trenches for the allies. Many of these men had never been exposed to the illnesses that the Western world had, such as influenza. My grandfather was first stationed in Egypt and then in France. In France he got sick and ended up coming back to New Zealand. He was fortunate because there were a lot of soldiers that didn’t make it back. So there is a ripple effect from these historic circumstances that have resulted in the possibility and slim probability of me being able to be born. I was also interested in that these soldiers journeyed all the way from Niue to be part of something greater than themselves. Visiting Mount Roskill was also a way to help the participants to gain their bearings of where they were in the city and to tap into their own memories.

Darcell Apelu, Generation Exchange (Auckland), 2016

a walking tour from New Windsor Road to Mangere Lawn Cemetery, 6:00-9:00 am, 1 October 2016

photo by Amy Weng

Darcell Apelu, Generation Exchange (Auckland), 2016

a walking tour from New Windsor Road to Mangere Lawn Cemetery, 6:00-9:00 am, 1 October 2016

photo by Amy Weng

B: Yes, people were able to locate themselves not just in terms of geography but also in terms of their own memories or stories. After this we followed the cycleway all the way down to Māngere Bridge.

D: On the way I shared how my father would cycle to Māngere to work at the freezing works coolstores when they were being built, and how he spent his school holidays working at the Colman’s Mustard factory and the Ribena factory. He was about fifteen years old at this time and the money he earned would be given to his parents. My dad would tell us these stories as a way to reinforce that his life’s work was for his family and to give his children opportunities. He was very proud of us but this was his subtle way of saying, ‘this is what I have done and look what you now have’.

B: We then continued on through Māngere Township and made our way to the cemetery.

D: Here I talked about my grandparents and my father who all struggled with cancer, and being aware that this could be a genetic implication for my relatives or me. For some people even talking about being sick is a real taboo, but not talking about something doesn’t make it any less a reality. I think that the people who participated in the walk appreciated that I was so forthcoming in acknowledging that while sickness is a scary and a difficult topic it is not something to be scared of.

B: In that sense, is Generation Exchange essentially an artwork that attempts to understand mortality?

D: Not in the sense you might be using the word. The word ‘mortality’ is often attributed a meaning that is definitive, but in reality mortality is more complex. Through sharing our experiences of death, health and wellbeing this complexity of life becomes more apparent and can enable us to collectively help each other. For me this has become apparent in seeing my dad battle cancer while I was making this work [in 2016] and after he passed away earlier this year [in 2017]. When someone passes suddenly it is hard to rationalise the loss because you are not given sufficient time to prepare yourself. In comparison, with my dad’s slow decline there was more time to consider these things. So by taking people on a long walk this provided an opportunity for the participants to engage with notions of mortality in an extended duration by way of conversation and retracing memories.